“My candle burns at both ends; it will not last the night; but ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—it gives a lovely light!”

“First Fig,” by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892—1950)

Our first week in the UK passes quickly, days and nights far too busy for mundane details such as jet lag. Our generous hosts, Phil and Jenny, include us in their dinner plans every evening and they also invite us to accompany them into London to see their youngest son, Jo, play a gig with his band.

We descend a staircase into a low-ceilinged West End club and find the place packed with adoring fans spanning a wide age spectrum, from twenty-something hipsters to—gasp—spectators even older than we are. When “The Travelling Band” takes the stage and the music starts, everyone in the audience begins singing and dancing along to what the BBC describes as “a shimmering blend of cosmic-country-pop, understated psychedelia, vocal harmonies and nu-folk.”

Dave and I sway to the beat, drawn in by Jo’s charisma and the band’s tight musicianship. Founded six years ago in Manchester, The Travelling Band, according to The Sun, “blurs the boundaries of folk/rock, delicately intertwining sensitive lyrics with accomplished folk vocals and jangly instrumental accompaniments to form a tapestry of glittering whimsy.” All that is true. Plus, the songs click into synaptic pathways and take hold; I’ve been humming Travelling Band tunes ever since the gig. Check them out at http://thetravellingband.co.uk.

By Friday, Dave and I are ready for an quiet evening “in.” But at the last minute we learn we are expected at Tom’s place (another of Phil and Jenny’s sons; they have five in all, plus a daughter) for pizza night, a weekly event. Family ties seem to be taken seriously here, as in France, with at least at least one day out of seven reserved for gatherings en famille.

And so we find ourselves in the renovated manor house that is home to Tom, Joanna and their four delightfully ebullient daughters aged 10 to 4: Daisy, Charlotte, Lola and Ruby.

A skillet of tomatoes and garlic simmers on the Wolf range. Neat mounds of pizza dough rest under a cloth on a marble countertop. I marvel at the brickwork detail of the soaring cathedral ceiling in the sleekly remodeled kitchen/great room. Tom tosses a round of dough high in the air where it twirls and expands before landing on his fingertips. Joanna puts together a salad with one hand while opening a bottle of white wine and helping Ruby warm a cup of milk with the other. (Moms must be the most skilled multi-taskers in the universe.) The girls take turns interviewing Dave and me and we return the favor, determining who is the most ticklish and who has the reddest hair (Charlotte, on both counts). Eleven of us, including Ben, actor friend of Tom and Joanna’s and unofficial uncle to the girls, congregate around the long wooden dinner table. We sample five varieties of homemade pizza, work our way through several bottles of wine, and bask in the general loving mayhem of extended family.

Then it’s the weekend. Dave and I plot a special outing each day. Saturday, after a pub lunch, we brave dark skies and a few raindrops to stroll through woods and fields and along a footpath beside the Thames.

We punctuate our walk with a pint in a pub, a habit that will quickly become a custom. A peaceful hour passes as we sit by the fire at the Nag’s Head, reading local papers, sipping local ale and anticipating an equally sedate evening ahead. Until Dave’s phone chimes with a text from Phil: “Impromptu Guy Fawkes party—fireworks and dinner—tonight. Will you join us?”

Closet introverts that we are, Dave and I worry we’re incapable of rising to yet another social occasion but we accept anyway. And are glad, for the evening proves both interesting and low-key; truly enjoyable. Phil is pouring champagne into fluted glasses when we walk in the door, and eighteen friends, relatives and grandkids roam the large house. Soon the crowd assembles outside on the terrace for an impressive fireworks display—yes, it’s legal here—launched from the tennis-court sized back lawn. Adults and children brandish sparklers while rockets whistle and explode overhead. After the show, everyone migrates to Phil and Jenny’s dining room for take-out Indian food.

Sunday, undaunted by chill, blustery wind and skies threatening rain (the weather has settled into a predictable pattern of clouds and drizzle which we already know enough to ignore—otherwise we’d never venture outdoors), Dave and I tour Hughenden Manor, home to Benjamin Disraeli “the most unlikely Prime Minister” from 1848 until his death in 1881.

Next on our agenda, a picnic in the Audi, sandwiches made from sharp cheddar cheese and tomato slices on seeded wheat bread.

Then a short drive to the starting point of a 3.5 mile circular walk around Chequers, the tranquil estate gifted to the nation in 1917 as a country retreat for the serving Prime Minister.

In the few day since we’ve arrived in Buckinghamshire—“Bucks” as the locals refer to the district—rain and cooler temperatures have hastened the leaf fall, and now, after a last glorious flash of color, bare branches begin to appear.

On the way home from our Chequers walk, we detour through a green and wooded vale into the picturesque hamlet of Whiteleaf.

For a pint, of course, at the White Horse Pub.

In the evening, we light candles, prepare dinner—roasted chicken, pasta with arugula, tomato and shallots accompanied by a simple green salad—and share a meal à deux in our “granny flat” for the first time. Seems like we’ve been on-the-go since the minute our plane landed, but looking back, we wouldn’t change a single instant.

A fresh pine staircase leads to our one bedroom flat over Phil and Jenny’s garage.

The main room is spacious and bright.

We never tire of our view overlooking Jenny’s well-kept garden and the Chiltern hills beyond.

Opposite the sitting and dining area, a modern kitchenette.

The bedroom features a down comforter and a super-luxurious Tempurpedic mattress.

This home-away-from-home suits us just fine.

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I,

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

—Robert Frost (1874 – 1963)

Dave departs for work.

I set off to discover more of the surrounding countryside. For the second morning in a row I run across a gentleman with a cane, walking his ancient snow-white Labrador.

“Hello again,” I greet him.

“Have you been walking ever since I saw you yesterday?” he jokes.

“Yes, just going ‘round and ‘round,” I smile. “Now I’m headed to Chesham.”

“Chesham!” he exclaims, bushy eyebrows inching upwards.

“Is that too far to walk?”

“Depends.” He says with a little laugh. “I don’t know how far you can walk!”

Neither do I, as we will see. Luckily, during our chat, this kind gentleman imparts a vital piece of information: the news shop in the village sells ordnance survey maps, exquisitely detailed area maps noting the location of every road, lane, public footpath and pub. After procuring said map, I embark on what I expect will be a two hour walk, home in time for lunch.

Two hours later, after tramping through leafy woods and narrow lanes, backtracking to make up for wrong turns and long pauses to decipher the ordnance map, I’ve barely made it a quarter of the way to Chesham, never mind the trip home.

It’s long past lunchtime. A brief consultation with my map reveals the hamlet of Ballinger Common not far ahead, across a grassy vale.

But the pub in town is shuttered and closed—for sale, in fact. I consider a bus ride home. But the schedule posted at the bus stop informs me the bus only runs on Wednesdays. (It’s Thursday.)

Famished and footsore, I stumble onward, making for the next nearest “PH” (public house) symbol on the map. Past the cluster of stone farms at Ballinger Bottom and the fine homes of Lee Common. About a mile later, I gratefully spy The Cock and Rabbit, on a tiny green called The Lee. I slump into a chair by the fire, thinking Ploughman’s Lunch, and maybe even a pint of ale. But I know there’s plenty of walking still ahead, so settle for a salad and a cappuchino. Afterward, I feel surprisingly refreshed and ready to tackle the footpaths again.

A country lane leads to a storybook view of pasture and woodland. Wooly sheep graze in the field. My route, a worn track in the grass, leads past these (harmless?) creatures.

They seem overjoyed to see me. A flurry of eager hoof beats, and a dozen or so fuzzy beasts trot over and peer at me as if to say, “Hi there! So glad you could make it. Please come in!”

I hesitate a moment at the gate, then lift the latch and enter the field. The sheep scurry aside to let me pass, then follow in line behind me. I stop, they stop. I walk, they walk.

Eventually they lose interest—or faith in me as their leader—and wander off.

A wooden stile leads to an adjoining pasture, signposted with a stern warning: Bull in Field; Keep Dogs on Lead. In no mood for a detour—there are only two good hours of daylight left, and at my snail’s pace I’ll need every minute to get home before dark—I climb over the stile hoping the sign is out of date, and the bull is not in residence today.

Keeping as much distance as possible between me and a small group of grazing cattle, I creep along the perimeter of the field and try to determine the gender of the largest bovine whose ponderous head has swiveled in my direction. The raincoat I’m wearing, I suddenly realize, is a bright shade of raspberry, eye-catching as a matador’s cape. Heart beating a tick faster, I pull off the jacket and turn it inside out so only the navy blue lining shows.

The bull—by now I’m convinced the one staring at me is male—stands rooted in the field like a malevolent sentry, gaze fixed on my timid progress. His harem of milk cows follows suit, and now an angry sea of bovine faces monitors my approach. A barbed wire fence borders the pasture, thwarting any hope of emergency exit. The bull lifts a leaden hoof and lumbers a few steps in my direction. I imagine my epitaph: Heedless American Woman Gored to Death by Bull in Field. Deciding I’d rather be dead-tired than literally dead, I retreat as swiftly as I dare (do bulls chase prey?) and resign myself to taking the long way around.

A half-hour later, thorn-scraped and sweat-soaked from fleeing mad cows and crashing through a grove of brambles and pine trees—surely trespassing on private land—I halt to consult the map and get my bearings. But the map is missing. I check each pocket twice, but the precious document is no longer on my person. Dropped, I presume, in my haste to escape the bull and his mavens. Sure enough, when I retrace my steps, I find the folded pages on the ground underneath the stile at the edge of the bull field.

The sun is beginning to set as I navigate the last hedgerows and fields outside Great Missenden. I trudge up Grimm’s Hill in the evanescent light just before dusk, grateful for the sight of home.

“Leave the wood through a wooden kissing gate, following a path gently rising through the field.”

From “Walks in the Chilterns”

Everything here is more wonderful than I could have imagined.

We live on Grimm’s Hill, within walking distance to the village shops of Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire. A few steps from our door, at the end of the lane, is a magical Beech tree wood.

Angling Spring Wood it’s called, and it is a beautiful, peaceful place, especially this time of year, when the delicate canopy of leaves glows with fall color.

Thick amber mulch cushions the ground. Rustle and flap of wings; a bird flushed from its perch. These are the woods that inspired Roald Dahl, resident of Great Missenden, to write children’s books such as “The Fantastic Mr. Fox.”

A visit to the local public library yields a temporary library card and a book describing scenic walks in the area. My plan is to explore the dense network of public footpaths—century old trails throughout England and Wales on which the public have a legally protected right to travel on foot—in the countryside around Great Missenden.

“Just past the farmhouse, when the road bends right, take the path on your left and pause to admire the view over the valley.”

The world is a blurred version of itself—

marred, lovely, and flawed.

It is enough.

—Jane Hirshfield

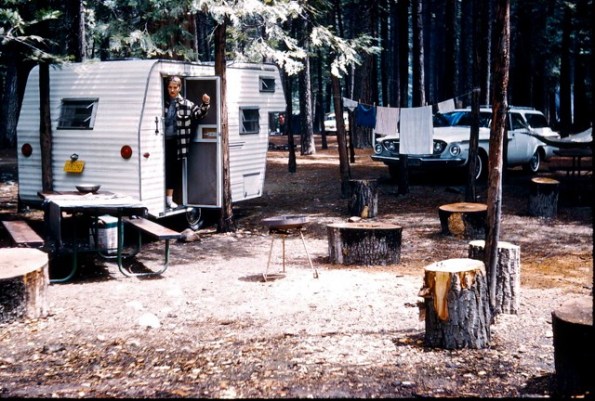

Truck and trailer crawl along the lip of the collapsed volcano. Milky fog obscures everything except the steep drop on both sides of the two-lane road. “This would be a good place for a guardrail,” Dave mutters as he gears down. Sleet smacks the windshield. Like Goldilocks’ porridge—first too hot, then too cold—the temperature has swung more than 60 degrees in 24 hours, from 90-plus in the high desert to near freezing at Crater Lake.

The clouds dissipate, revealing a landscape of desolate beauty. A cold, forbidding, other-worldly place. We park our rig, pull on jackets, hats and gloves, grab our cameras, hike up a short trail and peer into the yawning mouth of the caldera. Thousands of feet below, wind skids across the impossibly blue surface of the lake. Plumes of mist rise from the precipice. An uneasy sense of vertigo compels us to step back, away from the edge. This sensation of being off-balance, in danger of falling, stays with us the entire time we explore the crater rim, even when we are far from the brink.

When we’ve had our fill of fearsome splendor, we head down the western slope in search of a more temperate place to camp. On the way, we stop and walk Basil beside a forest stream layered with mossy rocks and ferns. A refreshing jolt of oxygen after the arid desert and the stark caldera. I feel I can breathe again.

We spend the night in a small, almost empty campground next to the Rogue River, in a grassy field shaded by tall poplar trees, yellow leaves scattered across the ground. Autumn, it seems, has well and truly arrived. Our thoughts turn toward home.

Morning dawns frosty, too cold to consider yoga outdoors. With husband and dog looking on, I attempt some asanas in the trailer. And manage a surprising number of poses and invented modifications, even in such a constricted space. “Trailer Yoga” video, coming soon from Amazon.com?

After a full day of driving we land at Lake Siskiyou campground in plenty of time to set up camp in a secluded site on the water with a view of Mount Shasta.

The heat of the day lingers. Dave sets off with his camera, disappearing into the pine, cedar, and maple forest. I swim in the lake. Basil barks at me from shore. We spend two nights here, catching our breath before pushing homeward.

As we buzz past Redding down Interstate 5, we discuss what most pleased and surprised each of us during the trip (see list below), and right in the middle of our conversation, the biggest surprise of all occurs. “What the…?” Dave stares out his side window. “There’s a guy…he’s waving at us…what is he…hey—it’s JOT!”

Pause for a moment to consider: Jot, bass player and vocalist, friend and band mate of Dave’s since college, lives near Los Angeles. The chances of him and Dave catching sight of each other on a highway far from anywhere must be nil to none. Suitably pleased and astounded, we pull off at the next exit, pile out of our respective vehicles—Basil too, tail wagging like a windshield wiper—and exchange exuberant hugs.

Jot is on his way to catch a plane, so we don’t have much time to chat, but as soon as we get back on the road I call his wife, Linda, and we spend a good while marveling at the synchronicity of two old friends crossing paths this way.

Continuing our lucky run of unplanned but perfect symmetry, we spend our last night on the road in the exact same spot where we began: in the Loch Lomond Marina parking lot. Even better, our dear friend Silva is free for dinner, and meets us at Sam’s in Tiburon. The weather is warm enough to sit outside on the deck, with a view of San Francisco skyline and city front. Feels like we’ve come home.

Dave enjoyments:

Taking photos

Playing guitar

New sights, new places

Spiritual uplift from nature

Snugness of cozy evenings in the trailer with wife and dog

Dave surprises:

Less time than expected spent outdoors at campsites

Portland—disappointment

Coos Bay—pleasant surprise

Anna enjoyments:

Walking in nature

Fears of claustrophobia not coming true

Overcoming challenges to practice yoga

Relative ease of procuring and cooking quality, healthy food

Bonding with Dave and Basil

Anna surprises:

The beauty of the Oregon coast

How many yoga poses fit into a 2 by 5 foot space

How little time our adventures left for reading, writing and quiet contemplation around the campfire

Bone-dry tumbleweed careens across the highway. We are traveling through the Warm Springs Indian Reservation, a vast high desert of parched canyons and grasslands adorned with rocks and scrub and an occasional pine tree. The weather forecast calls for a high of 90 degrees, inspiring us to change our plans for the night. Instead of camping on the outskirts of Bend, we push on, seeking cooler temperatures in the mountains.

Past Mount Bachelor, the scenery changes into a monotonous tract of pine trees bereft of undergrowth. Almost spooky. No flowers, no bushes, only spindly Lodgepole pines stretching away in all directions. Dark thunderclouds mass overhead.

Our destination is a series of campgrounds and volcanic lakes tucked into the eastern slope of the Cascades. The first place we try is closed for the season, the second is littered with slash piles. A dirt road leads to our third choice, a place called Lava Lake. By now it’s early evening. We make camp in a clearing of sparse pine trees, while a short but intense rain shower tamps down the dusty ground. Eager to stretch our legs after driving all day, we set out for a walk beside the lava-ringed lake.

Heavy gray skies threaten more rain. Hairy black moss cloaks the pine trees, as if someone has draped the boughs in mourning crepe. Dead trunks sprawl across the trail.

Dave turns back, leaving Basil and me to continue on our own. An eerie quiet pervades the sickened landscape. After about a half hour, Basil and I head back to camp too. This place will not be on our list of favorite campgrounds, but it’s better than sweating it out in the desert, and we’re that much closer to Crater Lake, next stop on the Odyssey.

We lunch in the yet-to-to-gentrified area of North Portland known as “Nopo,” in the garden of the John Street Café, and then set out to explore the city. We’d planned to spend two days here, but are dismayed to find a metropolis more sprawling, crowded and expensive than we’d expected. We stay in an RV park on the outskirts of the city, inserted cheek-to-jowl in a long row of gargantuan motor homes that make our 13-foot Scotty look more like a toy than a trailer big enough for two medium-sized people and one medium-sized dog. Signs posted every four feet along a perimeter fence alert us to Rules and Regulations particular to this place: No Dog Pee, No Dog Poo, No Parking, No Speeding, No Smoking, No Trash Dumping.

An hour later, we arrive at Trillium Lake, where we camp for the night.

We share the place with families, fishermen and beautiful big blue dragonflies.

Despite haze from a distant wildfire, Dave manages to make amazing photos.

Outside of Eugene, we pull into a service station and Dave gets out to pump gas. A grizzled gent sidles up and extends his hand. “Fill her up on your credit card?” Dave turns away, suspecting the guy is running a scam. “No thanks, I’ll do it myself.” The man shakes his head. “Not in Oregon.” A surprise to us, but since 1951 Oregon state law has prohibited self-serve gas stations due to a variety of justifications including the flammability of gas, the risk of crime from customers leaving their car, the toxic fumes emitted by gasoline, and the jobs created. The ban is as much a cultural issue as an economic one. “When babies are born in Oregon,” the service station attendant smiles, “the doctor slaps their bottom and declares, ‘No self-serve and no sales tax.’”

Thus enlightened and refueled we continue through the fertile countryside of the northern Willamette valley, past tidy barnyards and Christmas tree farms. Our destination is the temperate rainforest of Silver Falls State Park, said to be the most beautiful state park in Oregon. We are not disappointed. It’s midweek, and we easily find a peaceful campsite amidst tall fir trees next to a small creek screened by a lacework of bright green leaves. “The temperature is perfect here,” Dave exclaims. And it is. Warm enough to wear shorts and cool enough for Dave to build a campfire. He tries out his new guitar while I slice vegetables for dinner of stir-fried beef, green onions, string beans, and sweet bell pepper served over wild rice. Before long, I put dinner preparations on hold and join him outside. An hour passes while he plays guitar and we sing as many songs as we can think of. He’s right about the way his new Martin sounds—mellow, sweet and clear. I cannot vouch for our singing.

The next day we hike fern-lined paths shaded by moss-coated hemlock and tall Douglas fir. We view three major waterfalls, sparkling cascades diving off canyon walls two hundred feet high.

The waterfalls are indeed spectacular, but what I enjoy most about Silver Falls State Park are meadow marsh walks in the early morning and evening. Foxglove, Goldenrod, and Queen Anne’s Lace border the trail. I weave my way along the narrow, grassy track through waist and head-high foliage painted late summer gold. Basil gallops ahead, a white blur in the twilight. Rustle of birds in the undergrowth. Scent of damp earth. Basil doubles back to check my whereabouts, then dashes off again. A trickle of water. Closer inspection reveals a sturdy beaver dam. Whir of wings. Hum of insects. The secret aliveness of such a place.

“Smile, this is a friendly place,” proclaims a paper-plate placard as we enter an out-of-the-way mobile home and RV park about ten miles west of Eugene. Green lawn leads to the water’s edge and a wide-open view across the expansive Fern Ridge Lake Reservoir to low hills on the opposite shore. We stop here for the night.

The weather is pleasantly warm, in fact the hottest it’s been since Yosemite. We’ve been on the road about two weeks now, and it’s time for laundry (again) and a major reorganization of supplies in the Ford and the Scotty. Dave unpacks and re-packs the extra clothes, tools, food, fire and barbeque supplies stored in the truck bed while I clean and reorganize the dishes, clothes and foodstuffs we keep in the trailer. Later, I find a shady spot on the grass behind the trailer for some yoga. Afterward, I head across the road for a hot shower. All the talk of salmon fishing in the coastal river towns has given us a taste for the rose-fleshed fish, so for dinner we poach a little tail and serve it with garlic pasta and a simple green salad.

In the morning, we walk Basil along the shoreline. Six geese fly overhead, calling to each other with the wild, harsh sounds they make. “Like rusty gears that need oil,” Dave says.

In Eugene, we make three necessary stops: Home Depot, for a charger for Dave’s elecric drill, St. Vincent de Paul for a saucepan to replace the one I burned up, and—yes, you guessed it—a guitar store. Dave spends two hours looking at guitars and talking with the owner of the store before trading the guitar he brought with him on the Scotty Odyssey, a Bakersfield Telecaster electric, for an acoustic 1947 Martin that “sounds amazing.” He is beaming, light as air.

by Wendell Berry

“If you put it in the ground around here, it grows,” Harlea tells me. We are sitting on a swing in her flower garden, taking in a view of sweet peas, roses and cabbage-sized Dahlias, their petals colored ruby and persimmon. Dave and Walt sit opposite. Basil chases a tennis ball across the grass.

Dave and I have heard much about this Reedsport cottage and guesthouse, built in 1925 and renovated by Walt, where he and Harlea live when not in residence on their boat in Marin County. Lucky us, now we have the chance to visit. For dinner Harlea prepares a fresh garden salad, the best spinach Alfredo lasagne I’ve ever tasted and homemade blackberry pie with berries she harvested herself. Afterwards, the four of us retire to the guesthouse—a.k.a. music room—where Walt plays piano and Dave accompanies on guitar.

Our Scotty trailer is parked a few miles away beside a quiet creek in the North Lake RV Park, and so we return there to sleep.

In the morning, we five (counting Basil) meet for a walk around Lake Marie. Like a jewel in the forest, the lake is fringed with lush variety of evergreens, deciduous trees, rhododendrons, azaleas and ferns. A gallery of such leafy, multi-fingered lagoons populates the corridor of land between sand dunes and coastal mountains around Reedsport.

Tranquil and unspoilt, the area reminds us of the Lake District in England.

Off-leash, Basil disappears around a bend in the shady trail. A few seconds later he reappears, whizzes past, reverses direction and careens past us again, then doubles back to “buzz” us once more. Happy dog.

We depart Reedsport refreshed by the area’s natural beauty and grateful for time spent in the company of friends.

By now, all my internal questions of “Why are we doing this?” have receded into certainty: “Of course we’re doing this!” Whether due to time, habituation, or the benevolent inspiration of these wild places, I can’t imagine being anywhere but where we are, doing what we’re doing.

The sunny drive up Oregon’s south coast reveals wonder after wonder. Evergreen topped islands, crescents of beach and moss-covered woods, all cradled by vast blue sea and sky.

Just outside of Port Orford, we find the homey and bucolic Elk River Campground. A pastoral setting with clean bathrooms, free showers and even a wireless network. Many of the residents live here full time, the rest seem to camp here for several months during fishing season. Basil spends all afternoon lolling on the grassy field next to our trailer while I catch up on blog postings and Dave explores the village of Port Orford with his camera.

When the burly owner/manager of the campground, “Coot” is his name, finds out where we are from, he expresses interest—at arms’ length. “My daughter lives somewhere near Frisco—not sure where, never been there. She visits me here. I don’t go down there.” Into that den of iniquity, he might as well have added. I see his point. Easy to imagine how someone used to low population density and slow-paced country life would find the Bay Area with its seven million residents a bit overwhelming. Oregon’s entire population is less than four million, and over two million of those live in the Portland area.

Before departing the next morning, we take the time to hike around the point of land where the coast guard used to operate a lifeboat station.

Sunshine and warm temperatures bathe the landscape. Basil runs off leash.

Fir and broad-leaved forest gives way to a rocky promontory and sheer cliffs dropping away to the sea.

Twenty-five miles north we veer slightly inland and stop for the night at Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park. Many of the sites are already reserved or occupied at this pretty campground on this Saturday afternoon, but we’ve arrived early enough to find a shady spot near the Smith River.

Warm sun coats our backs for the first time since Yosemite. After making camp, we walk along the shore to the Stout Redwood Grove. Going is tough on the uneven surface of irregular stones, even for Basil. We throw sticks into the water for him to chase in lieu of a sorely needed bath.

A footbridge leads across the river to a grove of old growth redwoods.

As we enter the hushed presence of the great trees, the air cools, and our pace slows.

Even Basil treads at a more sedate pace than usual, as if he too is in awe of the ancient giants towering all around us.

For dinner, Dave gets creative: chicken thighs sautéed with mushrooms, shallots and wine accompanied by garlic pasta and steamed broccoli. Life on the road is getting better all the time.

A restful night’s sleep and an early start the next morning. We are eager to cross the border into our neighbor state to the north. Grassy verges of fireweed backed by tall stands of pine and fir flank the highway. Road signs announce odd place names that alternatively make us scratch our heads or laugh out loud: Wonder Stump Road. Humbug Mountain. Lost Man Creek.

A spectacular stretch of coastline and another sunny day welcome us to Oregon, a place we’re very happy to discover.

—Mary Oliver

Black crags called “sea stacks” dot the small bay, some shaped like giant shark fins. We park the trailer with a view of the ocean, and then hike down to the harbor.

Dave takes photographs while Basil and I chase each other along the scalloped shoreline.

Five miles further up the highway we detour again, into Patrick’s Point State Park, reputed to be one of the most scenic spots on the planet. We don’t plan to spend the night here, just take a look around, but the place draws us in. Set amongst stately Sitka Pine trees, close enough to the cliff edge to hear the surf far below, the campground is so tranquil, so utterly beautiful, that we cannot bear to leave.

We make camp in a peaceful spot, sharing the forest with only a handful of other campers. (Traveling after Labor Day has turned out to be an inspired decision.)

Sunlight burns through the fog for the first time in days. We lace up our walking boots and spend the rest of the afternoon exploring the rim trail around this enchanted peninsula.

A world of rock and sea, forest and mist. The woods are dense with ferny undergrowth, hemlock, red alder, pine and fir. Our feet tread paths carpeted by moss, fallen leaves and tree roots.

Early morning, still dark outside, I wake to the sound of seals baying off the point. Dave and Basil snore together in bed while I brew tea and type these notes. Yoga is not possible right now, just too cold and damp. I resolve to be flexible (NPI) and practice in the afternoon instead.

After breakfast, Dave walks Basil in the forest while I hike down to Agate Beach in search of a birthday present for Silva.

Ochre, green, copper and pearl-white stones color the long stretch of pebbly sand. I begin filling my pockets, searching for the most beautiful agate I can find. Each time I reach down and pluck a sea-smoothed gem from the beach I tell myself I’ve plundered enough of this shoreline, but still I continue, lured on and on by the possibility of a better, more perfect specimen than the ones I’ve already collected.

Finally, I force myself to stop. And then, as the aphorism goes, as soon as I stop looking, I find something even more perfect than what I thought I was looking for—a birthday mandala in the sand:

Morning dawns cold and damp (again), and I cannot face spreading my yoga mat out next to our rig in the chill morning on the available patch of dew-slick ground in full view of dozens of other trailers. But I am determined to practice, and obtain permission to use an unused room adjoining the campground convenience store. The carpet smells damp, and a large floor fan rumbles in one corner, but it’s still better than a public display on wet ground, so I stay.

In the college town of Arcata, we explore Tincan Mailman used bookstore, stroll around the town’s central plaza and lunch at a local pizzeria. Locals seem friendly and down-to-earth. Presumably, the pace of life here is more relaxed here than in the San Francisco Bay Area—maybe even more laid back than on the Central Coast.

Old town Eureka surprises and impresses us. A large, colorful harbor, Victorian architecture—sometimes outrageously ornate—and an historic central square surrounded by views of marsh, forest and farmland.

Not far from our campground, narrow lanes lined with wild radish lead to the shore where the Mad River meets the sea. Basil races over the dunes to the water’s edge. Excited by the wind and wild surf, he runs around in circles like a crazy dog. We three trudge far down the beach, then scale the dunes and return along the river. The sound of birds in the undergrowth. We follow a trail that winds through tunnels carved in the brambles past monkey flower, potentilla, purple asters, pale lemon beach Lupin and tall stands of thistles gone to seed.

Throw yourself like seed as you walk, and into your own field

—Miguel de Unamuno

“It’s so quiet,” Dave whispers upon waking. Indeed. Our campsite in Van Damme State Park is a slice of heaven any day, especially after the lively Cassini Camp. Our windows look out over a fairy tale meadow surrounded by spruce, pine and redwood.

We spend a day exploring the coast, starting with the village of Mendocino.

Strolling the streets with our cameras, we find much to admire in the historic architecture and weather-beaten charm of houses and storefronts.

At the far end of town, the Mendocino Headlands extend to the sea.

Raindrops splatter our truck’s windshield as we sit inside the cab eating sandwiches of avocado and sharp cheddar cheese on rye. Skies clear when we venture outside to explore the network of narrow dirt paths winding through tall blond grass.

Goldfinches cling to stalks of dried fennel. Basil runs free. He goes a little nuts, bounding and racing in circles as fast as he can. He is so happy, in such a pure state of canine joy, that to watch him transports us to a similar plane.

As always, when we find a place we like, we consider moving here. For about ten minutes.

Back at the campground, showers are coin operated—a new thrill for me—and I make the mistake of attempting one at dusk, after daylight has faded and before the automated lights have turned on. The room is so dim I can barely make out the wall-mounted coin meter. After feeding it with quarters, I turn on the tap and wait in the semi-darkness for the cold spray to heat up. Shivering and naked, I wait long enough to suspect hot water will not be forthcoming, and resign myself to a quick cold shower and no hair washing. Just as I’ve finished the deed, the water temperature warms slightly. A few more minutes and it’s tolerably hot, so I manage to wash my hair after all.

In the morning, treetops disappear into opaque mist. Dave drives to town in order to find phone signal for another business call; I prepare for another damp yoga session. My resistance to camping creeps back. Just a little. And just for a little while.

Today we will drive all the way to Eureka, through a patchwork of coastal hills, evergreen trees and fields of gold grass. Reminiscent of Northern Marin County, but far more vast and far less prosperous.

The Cassini Ranch Family Campground lives up to its name: boisterous groups of kids, parents and yapping dogs surround us. As soon as we park in our designated spot, a large, bus-like motor home pulls up beside us. The occupants promptly hook up to electrical power, turn on the TV and watch game shows. Since we too are connected to electricity—and internet—for the first time in six days, we take the opportunity to answer a few emails and learn what’s going on in the larger world.

The Cassini Ranch Family Campground lives up to its name: boisterous groups of kids, parents and yapping dogs surround us. As soon as we park in our designated spot, a large, bus-like motor home pulls up beside us. The occupants promptly hook up to electrical power, turn on the TV and watch game shows. Since we too are connected to electricity—and internet—for the first time in six days, we take the opportunity to answer a few emails and learn what’s going on in the larger world.

“Mom, where are the pop tarts?” This query, overheard the next morning, makes me smile. I carry my mug of tea outside in search of a flat spot to do yoga, and immediately notice the ground is not merely dew-soaked but sodden. A thick layer of fog obscures the hills, and a fine spray of mist—or is it rain?—floats through the air. The idea of spreading out my yoga mat is less than appealing. “Just a few asanas,” I tell myself. “If it’s really awful, you can stop.” And so I surrender to the damp. Curling forward into child’s pose, my shirt rides up and moisture coats the small of my back. But I persevere, and before long, the rain just becomes part of the practice.

The definition of Yoga I like best is “the discipline of conscious living.” When I started going to yoga classes, it seemed like a complicated system of stretches, a somewhat boring but effective way to mitigate muscle tension and stress. Eventually, I learned that yoga is much more than that. It’s the best way I’ve found to take the energy I normally expend on the world and turn it inward to nurture body, mind and soul.

Mid-morning, after a business call to a client for Dave and some time at the laundromat for me (our bag of dirty clothes, left outside overnight in a misguided attempt to make more room in the trailer, turned into a soggy mass by morning), we pack up camp and head north, hoping (in vain, it turns out) to see the sun.

At Fort Ross, we stop for a picnic in the trailer and a walk in the fog. The mist is so thick, I continuously wipe moisture from my glasses in order to see.

What might life have been like for the native people and settlers who used to live here? Less comfortable than camping in our little trailer, I think.

The time will come

when, with elation,

you will greet yourself arriving

at your own door, in your own mirror,

and each will smile at the other’s welcome

Excerpted from “Love after Love”

by Derek Walcott

Due to a change of plans, we spend the night in a parking lot. But not just any parking lot. A place we used to live, on our boat, not so long ago.

Due to a change of plans, we spend the night in a parking lot. But not just any parking lot. A place we used to live, on our boat, not so long ago.

After snugging the trailer into an empty corner facing open fields and wetlands, we walk the harbor with Basil. To our delight, we see our old friend and neighbor Walt is in residence on his hand-built sloop Mariah, and after much waving and hallooing back and forth between dock and shore, we climb aboard for a catch up chat. Before we part company, we make plans to meet him and his wife Harlea in about a week’s time, at their house on the Oregon coast.

By now it’s dusk. A line of ducks ripples across the harbor surface, trailing rivulets of silver into the reeds along the shore. We walk Basil on the levee trail and he scampers ahead, the white banner of his tail weaving through stalks of dried fennel. All three of us seem entirely pleased to rediscover this place. Did we make the right decision to move away? Could we live here on a boat again? Like Odysseus, we seem to roam far and wide in a protracted quest for home.

Dinner is simple and satisfying: pasta and homemade spaghetti sauce accompanied by arugula and romaine dressed with balsamic vinaigrette. Then it’s time to do the dishes: a careful operation involving an old plastic shower curtain spread across the bed—so we don’t drench comforter or mattress—and careful rationing of water so we neither deplete our fresh water supply nor allow the grey water holding tank to overflow.

Before going to sleep, we watch “The Thomas Crown Affair” on our laptops. Between our two computers, we have just enough battery power left to finish the movie.

Walker, there is no path,

you make the path as you walk.

—Antonio Machado

Two-lane blacktop threads through orchards of almond and pistachio trees, then dips and rolls across a sea of white-blond grass. We are on our way to Yosemite, the first stop on our month-long Scotty Odyssey. (Why “Scotty?” It’s the brand of our trailer. Why “Odyssey?” Because like Odysseus, we will journey far and meet challenges along the way.)

The seasonal creek at the edge of the forest still flows past our Upper Pines campsite, even now, in the first week of September. Wood smoke permeates the campground. We’ve arrived at the dinner hour, so after leveling the trailer and establishing camp, we attend to our evening meal: grilled steak, roasted potatoes and marinated string bean salad.

Early the next morning, I unroll my yoga mat next to the stream and practice asanas under the vaulted ceiling of pine tree boughs. Yoga in a cathedral.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about that feeling inside that prevents us from growing and taking risks. That feeling we call resistance. When Dave first suggested we buy a little trailer and go on the road for a month, I resisted the idea. But some internal tide slowly turned, and here we are. In the same way, I used to resist doing yoga (maybe because I knew I should do it), and I certainly resisted doing it first thing in the morning, but now I look forward to beginning the day by breathing my way into odd postures. One of my goals for this trip is to continue daily yoga practice. Stay tuned.

After breakfast (raisin bran and banana for Dave; yogurt, almonds and fruit for Anna) we stroll the valley with Basil.

It’s hot, close to 90 degrees, and we don’t go far before dipping into the chilled waters of the Merced. Water so cold it hurts, until feet and legs go numb. The current nudges me downstream. I anchor myself by grasping the round granite boulders beneath the surface.

In the evening, Lowell, and his friend Marjorie, whom we’ve long waited to meet, join us at our campsite for cocktails and hors d’oeuvres. They stay for two hours, which passes like two minutes. Marjorie is thoroughly lovely: bright, warm and unpretentious, and we look forward to seeing more of her. It’s obvious she and Lowell are very happy in each others’ company. We let them go with hugs and a date to meet the next day. They head to the Ahwahnee for dinner with friends. We stay in our campsite and heat up bean and sausage soup.

The following evening we join the party at the Ahwahnee. Cocktails on the terrace with Lowell and Marj and her friends from England, Virginia and Barry, an upbeat, erudite and socially conscious couple. Virginia, friend of Marj’s since college, is an accomplished classical flautist who is American-born, though has made her home in Hong Kong and Britain since the early 60’s. Her husband Barry is a former professor of Economic History at Cambridge and Harvard, and also a former director of a foundation that funds academic research. Conversation is easy and wide-ranging. We are the last guests to leave the dining room—to the waiters’ initial chagrin and eventual relief. The following evening we will happily gather again, around the picnic table at our campsite, and enjoy each others company until after dark.

On our last day, a hike to Vernal Falls bridge. Bay Laurel trees shade the trail and scent the air, reminding Dave of bay leaf infused stews. Mustard and russet colored leaves blanket the trail beneath our feet. The sound of flowing water is ever present. Yosemite, magical as ever, is especially memorable this time.

Shanghai astounds the senses. Ultra-modern skyscrapers contrast with leafy residential streets. Gardenia scented pathways lead past sidewalk grates wafting eau de sewer. Laundry hangs from every conceivable appurtenance, even tree branches.

Much of life takes place on the sidewalks, where residents socialize, eat meals, buy and sell wares, drink tea, play cards, offer repair services, take naps, shampoo their hair and sit down for a shave and a haircut.

TThe boundary of “personal space” is much smaller than the distance we maintain from each other in the west. Here, everyone jostles everyone else and expects to be pushed and shoved in return—no offense!

TThe boundary of “personal space” is much smaller than the distance we maintain from each other in the west. Here, everyone jostles everyone else and expects to be pushed and shoved in return—no offense!

Taxis, cheap and efficient, are ideal for getting around. Since none of the drivers speak English, we depart the hotel each day armed with a small rolodex of cards printed with Chinese characters describing the places we’d like to go, and—very important—a card printed with the name and address of our hotel, so we can find our way back.

I dress modestly and keep my hair in a bun, but my round eyes, tall stature and freckled skin stand out, and people sometimes stare. When I ask permission to take portrait photos, most residents seem happy to oblige, and pronouncing even the simplest phrase in Mandarin brings a big smile to people’s faces.

Most of the people I encounter seem relaxed and cheerful, less stressed and harried than the average American in a city of similar size. Incredible to realize that Chinese people my age, teenagers during 1966 to 1976, were shipped off to the countryside to work as peasants under Mao’s re-education program. Their parents, deemed intellectuals, suffered public humiliation, sometimes death.

A ferryboat plies the channel between Taiwan and Guanzhou. We are on board, about to arrive on the mainland of China.

We disembark into an airless customs shed and take our places at the end of a long line. A stern official hands us a Health and Quarantine Declaration Form asking whether we’ve had close contact with “poultry or bird in the past 7 days,” or had symptoms of “snivel” or “psychosis.” No, we report. We are neither flu-ridden nor psychotic, merely hot, tired and thirsty. Under the humorless gaze of armed military personnel, we grip our passports, sweat, and wait.

A minivan shuttles us to our hotel through streets congested with cars, buses, bicycles and scooters piled high with people, produce and all manner of goods.

Everything seems under construction, half-finished buildings sheathed in rickety bamboo scaffolding and piles of masonry on the sidewalks.

Armed military police are everywhere.

Checking into our hotel requires many smiling assistants and several cups of tea.

Funded by the Chinese government in order to woo foreign business investors, our hotel room is luxurious and squeaky clean. The view from our window looks out to an anomalous mix of dingy apartments and new high-rise condos.

Industry and housing in South China grow in tandem at an exponential rate.

We visit a range of manufacturers, from small assembly plants to high-tech factory/dormitory complexes with clean rooms, vast inventories, and housing for hundreds of employees recruited from the countryside to live and work on site.

The South China News headlines make for interesting reading (I did not make these up):

Woman With Big Appetite Goes to See Doctor

Man Talked out of Suicide by Helpful Granny

Gum Stuck in Buses Proves Tough to Clean

Dog Saves Owner, Dies Trying to Rescue Cat

We depart for Shanghai by plane from the Shenzen airport, a crowded, confusing and fascinating place where embarkation tax must be paid at a specific, difficult-to-locate desk, non-smoking and smoking areas are strictly enforced and the snack bar serves gorgeous asian pears.

October 2006

Wood smoke and smog obscure the Malaysian sky. “The Haze,” as it’s called, comes from industrial pollution combined with the Indonesian slash and burn method of clearing land to build new factories. Local residents suffer respiratory ailments; we feel the sting in our eyes and throats.

Just before dawn, we wake to the amplified sound of a man’s voice floating over city rooftops, rising and falling in the haunting, sub-tonal chant that is the Muslim call to prayer. Five times each day, loudspeakers broadcast this musical prayer from every Mosque, admonishing the faithful to look to Mecca and give thanks to Allah. All work ceases for a few moments, as everyone expresses gratitude.

We have one day in Penang. Dave inspects factories, conducts business on the golf links and gets caught in a downpour.

I hire a cheerful Malay driver, “Joe,” to show me, and my camera, around.

Eggshell haze obscures the sun, but the day still radiates heat. Our first stop is a traditional Malaysian fishing village.

Fishing, it turns out, is Joe’s favorite pastime.

Our next stop is a Chinese mansion dating from the late 1800’s. No air-conditioning, but it’s still cooler inside the thick stucco walls than outside in the tropical glare.

I explain to Joe that what I really want to see are historic neighborhoods where people currently live, not museums where people used to live, so Joe drives me to the old town, a labyrinth of one-way streets lined with houses dating from colonial times. The narrow lanes leave no room for parked cars, and he suggests I roam on foot. “No worry,” he says with a reassuring smile, “I find you later.”

Left alone on a deserted corner in a warren of run-down lanes, I feel as if I’ve stepped out the car and back 100 years in time.

Simple row houses line both sides of the street, some restored and freshly painted, others in various stages of crumbling decay. All are inhabited, even the most decrepit.

A thin sheen of perspiration coats my skin. After wandering for a half hour I turn a corner and slide gratefully into Joe’s taxicab, idling at the curb.

On the drive back to the hotel, Joe and I attempt to converse in pidgin English. I ask if he believes in a specific religious faith, expecting him to say he’s among the 60% Muslim population. His answer surprises me. “No, I am alone,” he answers in his broken English, “I mean not follow Allah or Buddha; no God. My religion is my wallet full.”

Trailer in tow, we pull up to the ranger’s hut without a reservation and are assigned a campsite with a million dollar view: the wide blue horizon of Monterey Bay. An auspicious beginning for our first trailer trip. In preparation for this day, we’ve spent hours darting back and forth between house and trailer; assembling, packing, testing and arranging our shelter on wheels, plagued (speaking for myself) with start-up angst over what will be necessary, what will be desired, and what will fit.

Since space is at a premium, we’ve limited personal effects to the bare essentials: quality wine glasses with stems, a selection of poetry by Oliver, Frost, Kunitz and Yeats, Grandma Suzy’s guide to Pacific Coast Wildflowers, and Sibley’s Guide to Birds.

Our first meal cooked on the two-burner gas stovetop will be curried lentil, kale and sausage soup. I put the pot on to warm, and as soon as steam escapes from under the lid, the smoke alarm goes berserk, emitting a series of high-pitched shrieks. Basil barks to let us know something is wrong, as if we didn’t know. Dave flings open the trailer door and I fan a potholder under the sensor. It goes silent for about three seconds before blasting another round of ear-stunning screeches. Dave yanks out the battery and disables the thing, muttering that if something catches on fire, we’ll surely know.

After dinner, we walk the dog and then sit by the campfire. An experienced camper, my capable husband is dressed appropriately for the outdoors, but due to oversight or inexperience I am wearing little more than yoga gear. (Sleeveless cotton shirt and Capri leggings? What was I thinking?) Basil too, is shivering. He sits on the ground next to my chair, his dark brown eyes imploring me to stop this nonsense and go home where it’s warm. I pull him into my lap and huddle closer to the flames. For a dog who lives in the present and divides the world into two categories—threatening and non-threatening—the line between novelty and apprehension is razor thin, and this strange new activity represents a frightening departure from the norm. For me too, but being human, I understand that camping, by definition, is uncomfortable. That discomfort is part of the reason we do it; to remove ourselves from the familiar, to form new neuronal connections, to seek inspiration, and to come back renewed. Or so I keep telling myself.

The night is cold, and we sleep fitfully on a mattress that spares no mercy for hips and shoulders. In the morning, my neck aches. A cold film of condensation coats the windows. The water view has dissolved into gray mist, and a faint tapping on the trailer top turns to steady rain.

The good news is that we have spent the night at a campground a mere two miles from home. After breakfast, we return to the house for the things we’ve forgotten (raingear and winter clothes, for me) and then head for Target for a few last items on our list. Shopping takes longer than we’d planned, and when we’re done it’s lunchtime, so without further ado we repair to the trailer for sandwiches and cappuchino. Right there on the blacktop overlooking parked cars and bright red shopping carts. Convenient, inexpensive and delicious. I’m liking our snug little trailer more every minute.

On the road for real, we roll through hilly grasslands dotted with oak trees and livestock, blue skies overhead. We keep a sharp lookout for patches of color signifying wildflowers, and are rewarded with an underwhelming display. No matter, the drive is easy, the landscape green (this time of year, anyway), and the trailer bumps sweetly behind us.

At the Pinnacles campground, we find our designated site at the edge of a large field. I am charmed by our expansive view of green valley and jagged hills, by the sound of quail yodeling in the undergrowth, and by fact that we can plug into an electrical outlet.

But Dave frowns. “There aren’t any trees. This site is completely exposed.” He grimaces. “And we’re in RV Land.”

True enough, the campsites near us are occupied by large motor homes, and our site is far from tree or bush.

But there’s no better site available this night, so we park the trailer and set up camp in the meadow. I spread a red and white checked cloth over our table and unfold two chairs. Basil, nose twitching, velvet ears attentive, roams the campsite as far as his tether allows. Quail forage in the grass not five feet in front of us. In the distance, Condors circle rocky peaks. We sit, enjoying the view, the quiet, and the feeling of having arrived.

Without warning, a horde of kids spills into the meadow, wave after wave of adolescent campers followed by a handful of young adults. They divide into teams and begin playing a series of games that require much shouting and running around. So much for peace and quiet. I don’t mind. The place is still beautiful. And it’s all part of the adventure.

Dusk approaches, and the junior campers file out of the meadow. I unroll my yoga mat on a flat patch of ground and Dave takes Basil for a walk. A cool breeze combs the grass. I worry I will feel awkward and distracted practicing yoga out of doors in plain sight of anyone who happens to be looking. But the opposite is true. The fresh air seems to magnify each sensation, and I don’t care if anyone is watching. Each muscular contraction and release, each inhalation, each exhalation, feels more invigorating than the last.

When I return to the trailer, dinner is almost ready: sautéed fingerling potatoes and sausage accompanied by a salad of red-leaf lettuce, chopped carrots and balsamic vinaigrette. The wind has strengthened and chilled, so we dine inside. We pour boxed Malbec into stemmed wine glasses and use our amber table light for the first time. It casts a warm glow.

In the morning, Dave and Basil explore the labyrinth of tent campsites and report a large selection of tree-shaded spaces available. No hook-ups, but we are willing to relinquish electricity for ambiance, so we embark on a quest for a more gemütlich spot. At each potential site we consider the aesthetic appeal and the je ne sais quoi of gut feeling, then weigh practical concerns such as proximity to neighbors and restrooms, amount of level parking, shade versus sun and site orientation. “Camp site selection,” Dave declares, “is both art and science.” We narrow our selection, review our options, and decide on a secluded clearing shaded by four giant valley oaks.

After establishing our new campsite, Dave and I fortify ourselves with a snack of Gala apples and almond butter on whole grain bread and depart for a hike to the Pinnacles Overlook. Basil must wait for us in the car, windows cracked wide, as dogs are not allowed on any of the trails.

We climb for an hour on a sun-baked trail. Early on, we shed coats and stash them behind a rock, and Dave rolls up his jeans as if digging for clams. We continue past Manzanita bushes, flowering Indian Paintbrush and boulders daubed with rust and mustard-colored lichen. In a few places, oily poison oak leaves stray across the trail. I keep watch for snakes, and sight a tail-tip sliding off the path into tall grass. At the overlook, Dave composes a few pictures, but overall finds the lighting and scenery less than inspiring.

Basil is happy to see us return. The temperature inside the car is warm but not hot, and I am relieved to see he shows no signs of distress. Any later in the day, or in the season, we wouldn’t dare leave him there.

The rest of afternoon we relax under the lattice of tree limbs shading our site. A colony of Acorn woodpeckers inhabit the trunks and branches surrounding our camp. I like the tapping noises they make, and Basil doesn’t seem to mind, even though it sounds like someone is knocking at the door, usually a hot button for him.

In the early evening, deer graze on the hillside. Basil barks at them, but stops when we tell him to. Dave builds a bonfire and we set the table for dinner outside. Anna’s goulash, wide egg noodles, green salad, baguette and Emmentaler. Still working on that box of Malbec.

Just before nightfall, we take Basil on a long walk around the campground. He sniffs incessantly. A wild rabbit feeds in a clearing. Basil spots it. The hair rises along his back and he strains at the leash. White cottontail disappears into the undergrowth.

Early the next morning we head for home, shakedown mission accomplished. We’ve practiced setting up and breaking down camp three times in three days. We’ve figured out the best system for washing dishes and where to put clothes. We’ve determined that the seldom-used microwave makes a good breadbox, and that we need a layer of foam under the mattress. We’ve started a “to do” list for our next trip. Best of all, I’ve discovered I like trailer camping more than I feared I wouldn’t.

Back in Capitola, Dave and I unpack and wash down the trailer while Basil curls up on the couch and takes a five-hour nap.

Now that we have a trailer, Dave is eager to revive the family tradition of camping in Yosemite. He searches online for available campsites—a bit like hunting for hidden treasure, or in this case, cancelled reservations—and finds two consecutive mid-week nights in the Upper Pines campground.

As our departure date nears, we grow increasingly uneasy about the suitability of our Nissan X-Terra as tow vehicle. Dave recalls a nerve-wracking drive to Yosemite in the early sixties, when his dad rented a small travel trailer and pulled it behind their 1962 Dodge Dart. As they navigated the narrow, curving road into the park, Dave feared at any moment he’d hear metal scraping rock as the trailer sideswiped the stone guardrail, or metal tearing into metal as they collided with an oncoming car. Neither catastrophe occurred. But the indelible imprint of childhood terror plays a role in our decision to trade in the X-Terra for a Ford F-150 truck.

We pack up the night before so we can get an early start, are delayed in the morning by technical difficulties unworthy of explanation here, and end up hitting the road a couple of hours later than planned. No matter. What’s important is that the new Ford proves eminently suitable as tow vehicle: no longer does the trailer wag the truck, we aren’t worried the engine will overheat, and—bonus—Basil can ride up front on the bench seat without squishing me under thirty-five pounds of terrier hound.

At lunchtime, we pull off the highway next to the San Luis reservoir and make sandwiches in the trailer. Instead of Target’s red and white logo—like the last trip—we gaze at an immense cache of blue water spreading across a hollow of ochre-dry grassland.

Our journey continues across the vast (very vast) and flat (very flat) San Joaquin Valley. Basil reclines on the seat between us, his head resting on my lap like a velvet paperweight. As we approach the foothill town of Mariposa, the landscape begins to dip and roll. Spring pastures burn from green to gold, lupine and poppies gather in shallow pockets, and clumps of lichen-covered rock jut from the ground like giant’s teeth. In the distance, a suggestion of our destination: the dim outline of snow-topped peaks.

“Here we go,” says Dave. We climb to Mid-Pines, and then wind our way down the steep grade to the Merced River. I’m glad of the sturdy Ford, and glad I’m not the one driving.

At the park entrance, a khaki-clad ranger leans close to the truck window and starts explaining how to find the campground. Dave smiles and confirms he knows the way. We squeak through Arch Rock, crawl down the final descent, and then we are in the valley.

Waterfalls seem to tumble from every cliff and fissure. Chartreuse buds illuminate filigree branches, and dogwood blossoms open to the sky. It’s easy to see why the Indians called this place sacred.

Dave cruises at a sedate pace through Upper Pines campground, past a hodge-podge of tents, motor homes, and a panel truck filled with camping gear for a group of teenage kids. Our site perches on the outermost loop, at the edge of a forest glen. We are enchanted. Rust-colored pine needles coat the spongy ground, and a seasonal stream rustles past, cascading over rocks and branches with a sound like a contented sigh. Half Dome towers overhead, watching over fortunate pilgrims who sleep here.

After settling in, our first act is to tour the campground. Ostensibly we are walking Basil, but actually we are conducting a covert survey. Campsite selection, as noted in our Shakedown Cruise, is an important ingredient of every trip, and seems to be one of our favorite pastimes. Notebook in hand, we record the number of each particularly appealing site and then rate it on a scale of 1 to 10. (This meticulously researched list available by request.)

The evening is mild, and we eat dinner outside: turkey burgers spiced with shallots and herbs accompanied by sautéed asparagus, carrots and broccoli rabe. In the site next to ours, four cheerful young men sit around a blazing fire. Two of them are identical twins, celebrating their 30th birthday(s). They have brought a boom box, and are playing Eagles songs from the 70’s. “Is the music bothering you?” they ask. “No; no,” Dave assures them. “I like it.” (The Eagles are a favorite band since college.) After dinner, one of the twins, baseball cap worn backwards, walks over and hands us a paper plate with a generous slice of birthday cheesecake. “Sure the music’s not too loud?” he asks again. No worries. We remember what it’s like to turn thirty. Besides, the party mood is contagious.

In the morning, we wake to the sound of water flowing in our little brook, and sunlight reflecting off the granite wall of Glacier Point. We plan an early hike to Mirror Lake. The air is cool in the pines on the valley floor, and the Girl Scout in me layers on wool hat, long pants, fleece and polypropylene. Dave is similarly prepared.

Over-prepared, it turns out, because as soon as we start walking, we begin to overheat. “We have to remember to start out cold,” Dave says. As if to illustrate this precept, an incongruous apparition appears on the trail: a plump blonde woman wearing a skin-tight mini skirt, spaghetti-strap top and knee-high rubber boots. She looks completely out of place, but certainly not overheated, and for one cognitively dissonant moment, I covet her outfit. Well, not the boots.

At the lake-becoming-a-meadow, we rest in the shade. Dave takes off his shoes and socks and dips smooth white feet into the water. With a startled yelp, he quickly pulls them out. “Too cold!” He cries, wiggling his dripping toes. “Like sticking my feet into a gin and tonic.”

We return to camp, and all is quiet. After a lunch of open-faced sandwiches (sautéed greens, slices of avocado, Emmentaler and tomato on dark rye bread) we arrange chairs at the edge of our snow-fed creek. Basil naps at our feet. We watch patterns of light shift across the forest floor. Two ducks float past. They dive to search for food, then surface and drift further downstream. Sitting here, you’d never know the valley is full of people. I’m accustomed to seeing as many tourists in Yosemite as awe-inspiring views, but this trip we’ve stayed away from high-traffic areas, and since we’ve brought our own food and lodging, there’s no need to visit the teeming hotels and restaurants. I am experiencing the park in a new way; enjoying the serenity of self-sufficiency. I wish we could stay longer.

As if reading my mind, Dave proposes we stay another night, if we can find an available campsite. A quest begins. Fifteen minutes later, we are sitting in the truck in the Lodge parking lot, trolling the website on Dave’s laptop. No vacancies. At least not right now. Maybe after a walk to Yosemite Falls. Eagle Scout Dave pulls on a waterproof jacket and hands me a raincoat, even though skies are clear and the day is warm. This time preparedness pays off, for at the base of the falls, the explosive force of the water creates a localized storm of icy, wind-driven mist.

Back at the Lodge parking lot, we check the website again, but nothing has opened up. Disappointing, but not surprising, Dave informs me with a sigh. People reserve months in advance to be here now, when the weather is mild, the dogwood blooming, and the waterfalls at their peak. “But,” he brightens, “there’s still a chance somebody won’t show up tomorrow.”

In the evening, wood smoke wreathes the trees. Dave grills steaks while I roast fingerling potatoes and toss a green salad. We sip glasses of Yellowtail Shiraz and eat outside at the picnic table, at home and secluded in our personal space, yet in relative proximity to hundreds of other campers doing the same. It’s more peaceful than I might’ve predicted. There’s a comforting spirit of “circling the wagons,” and although no physical barriers separate individual sites, unwritten protocol seems to decree that everyone take pains not to tromp though anyone else’s domain or otherwise invade anyone else’s privacy.

The next morning, we walk to the ranger’s kiosk and inquire about the availability of “no-show” campsites. A grizzled, jug-eared gent dissuades us. Sign-ups started at 8:30 a.m. (an hour ago), the verdict won’t be announced until 3 p.m. (we still have to vacate our site by noon), and some of the sites are closed due to flooding, thus lessening our chances. The best thing to do is to make the most of the time we have. Good advice any time.

On the bridge over the Merced River, we pause to admire the volume of water passing under our feet. In Lower Pines campground—you guessed it—we scout appetizing sites for future reference. Across the bright ribbon of Tenaya Creek, we skirt the valley on an oak and cedar-shaded trail.

Basil tries to chase about fifty squirrels, but is thwarted by his leash. Water spills across our path under the Royal Arches, and the three of us leap from rock to rock. Near the Ahwahnee Hotel, we photograph a magnificent grove of dogwood trees in full flower. The only other soul we meet is a squawking Stellar Jay, and we feel as if we have the valley to ourselves.

We will return in September, and have already extended our campground reservation from three nights to five.