DAY FIVE: MONUMENT VALLEY

Our “deluxe” 3.5 hour tour of Monument Valley is scheduled to begin at 7:45am. But punctuality, it seems, is unnecessary, for our guide is nowhere to be seen. While we wait, we become acquainted with our fellow tourists: Joel and Megan, a twenty-something couple who are tent-camping their way across the USA from the Pacific Northwest to Florida, and Stacey, a woman about our age whose husband has stayed behind in their motor home with their two Australian shepherd dogs. At 8:15, an open-sided truck pulls up next to us and a wiry Navaho man climbs out of the driver’s seat. “I’m Ray” he says, offering us a toothy grin and ushering us into the back of the vehicle.

We bump along dusty desert backroads with periodic stops at prescribed photogenic viewpoints, and if we bang the side of the truck hard enough to get Ray’s attention, he will make an unscheduled stop.

We admire the desert’s wind and time-sculpted features, and thrill to see ancient pictographs.

As a special feature of our “deluxe” tour, Ray brings us to a Navaho homestead of round, dirt-covered dwellings called “hogans”, traditional structures constructed by driving logs vertically into the sand, building an interior log framework and covering it over with mud and sod.

A local woman joins us and explains Navaho rug weaving, soap making (from Yucca roots) and basket weaving.

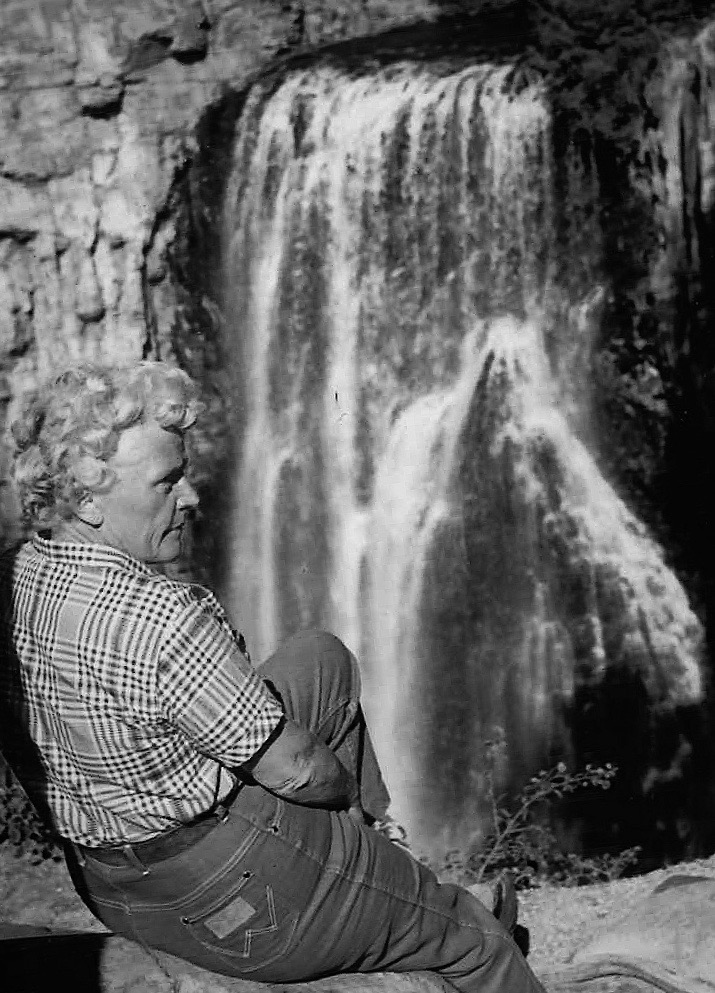

“The theme song from Gilligan’s Island keeps running through my head,” laughs Megan as the truck bounces along an especially rutted dirt track. I think about how the dusty, spine jarring ride reminds me of childhood jeep trips with my grandpa in the back country of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Those forays always seemed to involve at least one instance of getting stuck whilst fording a creek or driving through a snowbank. Little chance of that happening here, I tell myself.

But I am about to be proven wrong. Traversing a sandy valley, our rear end skids sideways, Ray accelerates and our wheels spin, digging into the soft ground. We are stuck. Ray tries to shift into his lowest gear, but seems unfamiliar with the procedure. “It’s my second day on the job,” he confesses. Joel shouts helpful instructions to Ray—stop, shift into neutral, then low four-wheel drive—and then yells at us to rock back and forth in our seats, and finally the truck gains forward momentum.

As we near the end of our tour, Ray speeds up, and the truck jounces us around like a bucking bronco. We suspect that he has noticed he’s behind schedule. “Chiropractor appointment needed after this tour,” shouts Stacey as yet another jolt lifts us clear off our seats and slams us sideways.

After four scenic hours, we clamber out of the truck coated in red desert dust, but with (hopefully) all our vertebrae intact.

DAY SIX: GOULDINGS to MOAB

On the drive to Moab, our dance card is full of sights to see. First stop is a place on the map called Mexican Hat, and there’s absolutely no doubt about which rock it must be.

Our next waypoint is Goosenecks State Park, a vertigo-inducing overlook of entrenched meanders in the San Juan River. Formed by flowing water and geologic forces over millions of years, the canyon walls tower over 1,000 feet above the river and reveal ancient rock layers of sandstone, shale and limestone.

We consider our next move. Are we up for the adventure of driving an hour round trip out of our way and hiking two miles roundtrip to see Anasazi ruins called House on Fire? We are. The trailhead is unmarked, and we set off on a pleasant trail along a dry river bed only 70% sure we are on the right path.

Our (semi-blind) faith is rewarded, and we eventually come upon ancient stone structures tucked under the overhang of a huge rock. Built of stacked stones 700—1,000 years ago, these shelters were probably granaries, used by local inhabitants to store corn and other foodstuffs. They are called “House on Fire” because the coloration of the rocks gives the illusion of flames streaking from the roofs.

Hot and tired, but feeling a sense of accomplishment, we return to Suzy and continue our drive to Moab.

Instead of staying in town, we’ve booked an Airbnb in a place called Pack Creek Ranch. The directions instruct us to turn off the main road onto an unpaved, gravel-strewn track that appears to lead up a canyon into wilderness. No sign of any inhabitants other than free-range cows—many with newborn calves—who graze near the road and stray into our path. We proceed with caution, dodging livestock, kicking up dust and beginning to wonder if this Airbnb is such a good idea.

All misgivings vanish as we round a bend and glimpse our destination, a lush oasis of towering Cottonwood trees sheltering a handful of vintage log cabins grouped around a large lawn, reminiscent of an English village green.

We transfer a few items from campervan to cabin and then retire to the two comfy rocking chairs on the generous front porch. Years ago, some romantic soul planted lilac bushes around the perimeter of our cabin, and their perfume scents the air.

DAY SIX: MOAB

“I can’t believe that we’re in the middle of nowhere and the traffic is as bad as in the Bay Area!” Dave curses in downtown Moab as he waits to turn left at an intersection with no left turn signal and an endless line of trucks, cars, and jeeps heading toward us. Traffic jams in the desert? Who knew? We had planned to tour Arches National Park, but an unmoving queue of cars, RV’s and ATV’s clogs the approach, and a large sign informs us that timed reservations are required. We have no reservation, timed or otherwise, and a quick check of the National Park Service website shows none available today or tomorrow. We are defeated, but not particularly disappointed. We have already begun to anticipate a mellow afternoon back at our ranch.

Anna practices yoga on the green and Dave plays guitar. Later, we enjoy a simple dinner of shallot-infused burgers and a spring green salad.

DAY SEVEN: MOAB to VERNAL

In the early morning, goldfinches chatter outside the window. Perhaps they are discussing the change in the weather from warm and sunny to breezy and overcast, with thunderstorms predicted. We depart after breakfast, relieved to leave the bustle of Moab behind, and settle in for a longish day’s drive. The terrain varies but ultimately exhibits more of the kind of scenery we’ve seen for the last six days: high plains occasionally broken by juniper bushes, knobby layered cliffs, dry mesas and distant hills. Most beautiful today are the gorgeous cloudscapes softening the bright cobalt sky.

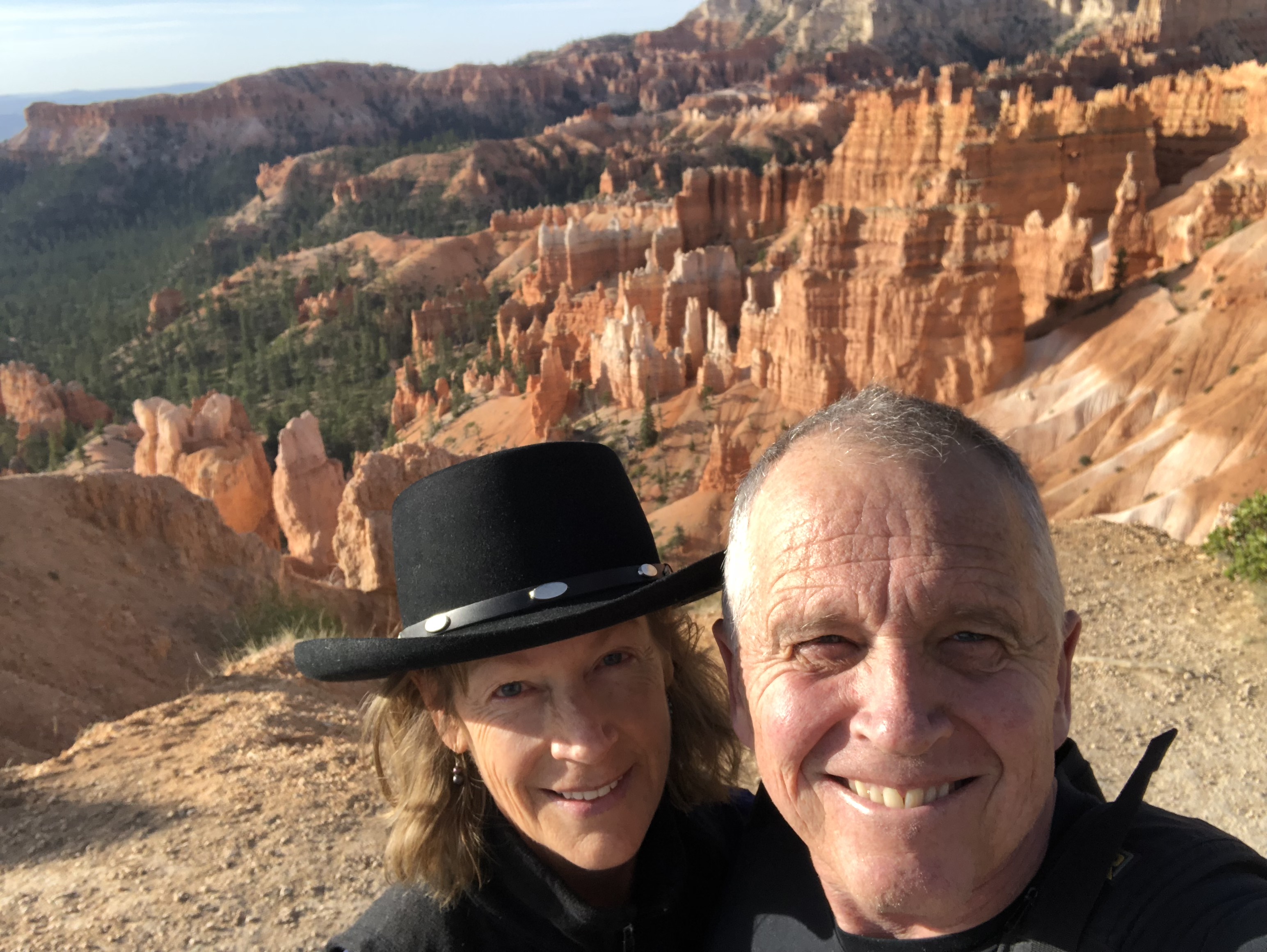

Our destination is Dinosaur National Monument, a place I have wanted to visit since my high school biology teacher (the brilliant and entertaining Ed Holm) described its wonders in one of his lectures. Dave is willing to humor my long-held ambition, and as we near this very out-of-the-way place, I wonder if it will live up to my expectations.

But I needn’t worry. A shuttle delivers us to the exhibition hall, a huge glass-sided structure enclosing an entire hillside littered with embedded dinosaur bones, and it is every bit as impressive as Mr. Holm promised. We are gazing at the fossilized bones of dinosaurs who died beside a dry riverbed during a period of drought 150 million years ago. The time scale itself boggles the mind. As does the knowledge that dinosaurs lived on the earth for far longer than humans have.

Between 1909 and 1924, over 350 tons of embedded dinosaur bones were excavated from this site. Photos in the visitor center show the magnitude of the original hillside and the scope of work required to unearth and transport the treasure trove of fossilized bones.

Browsing in the gift shop, we are both drawn to a tempting array of toy dinosaurs. We comb through the large selection of prehistoric beasts and finally manage to winnow our choices to two—Stegosaurus, an herbivore, and Allosaurus, a carnivore—for our two grandsons, aged 17 months and almost 3 years old.

“These little dinosaur models must be big sellers,” I comment to the young clerk as he rings up our purchase. “Oh yes,” he nods, then, with an impish grin he asks, “Would you get the reference if I said ‘Curse your sudden but inevitable betrayal!?’” Our blank faces must telegraph our ignorance, for he explains that it is a famous line from a TV show called Firefly, delivered in response to a sudden attack by an Allosaurus dinosaur. Enlightened by this knowledge that we might (or might never) use again, we thank him, head to the parking lot, and make our way to the town of Vernal.

The call of an American Robin welcomes us to our peaceful KOA campsite. A green thicket of scraggly bushes and Cottonwood trees borders our site.

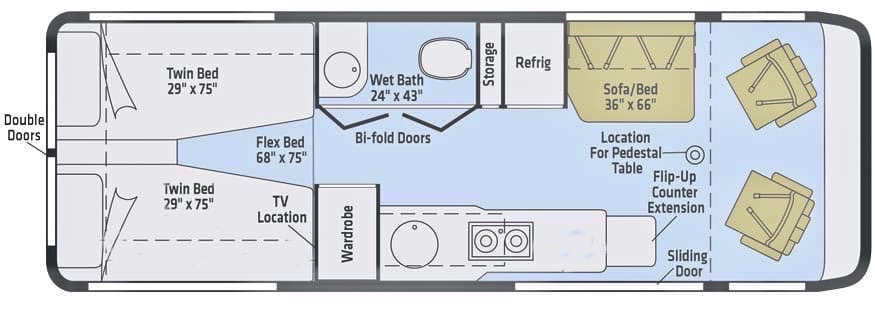

As I prepare dinner—prosciutto tortellini with marinara sauce and a salad of spring greens and chopped olives—I realize that the previous two nights in a rental cabin—no matter how charming—have served to remind me how much I appreciate the simplicity of the small, comfortable world of our campervan. It’s a tiny oasis of harmony. Finite in its dimensions, but wide open in its possibility for adventure.

DAY EIGHT: VERNAL to SALT LAKE CITY

We wake to blended birdsong (my Merlin App recognizes Black-capped Chickadee, California Quail, American Robin, Red-breasted Nuthatch and Yellow Warbler!) and the gentle of tap of rain on the rooftop. The rain continues all the way to our destination of Salt Lake City, but we don’t mind, the moisture feels welcome.

A flat landscape of juniper and sage gives way to bare hills, colonies of spindly white Aspen, patches of snow on bare ground, and in the meadows, the vivid flash of willows.

Our journey comes to a close, but leaves an indelible impression. In the vastness of the desert, surrounded by visible traces of geologic time and landscapes more beautiful—and fantastical—than we could imagine, we felt small and insignificant, and at the same time, connected to everything. Perhaps that’s the best part of time spent in any sort of wilderness; the ego takes a back seat to wonder, and we are reminded that in grand scheme of things, though we are tiny, we are part of a greater whole.

“…the strangeness and wonder of existence are emphasized here, in the desert, by the comparative sparsity of the flora and fauna…” —Edward Abbey, “Desert Solitaire”

I have never been a huge fan of the desert, but I am open to the possibility. The question is whether or not a camping trip in the arid wilds of Arizona and Utah will convert me.

DAY ONE: CALIFORNIA to ARIZONA

A two-hour plane flight from San Francisco delivers me to Phoenix, but the journey is not over yet. I open my Uber app, and soon am speeding away from the airport in a white Chevy Malibu piloted by Dean, a cheerful, middle-aged fellow sporting a goatee and a blue and white baseball cap on his close-shaven scalp. “I love Phoenix,” he declares as we depart the sprawling desert town, nary a tree in sight. “What do you love about it?” I ask, and he recites a litany of dubious claims. I remain unconvinced. He points out the giant Saguro cacti dotting the landscape and informs me that the cacti with the most “arms” can be up to 150-200 years old. They bloom mostly at night, according to Dean, and their main pollinators are bats, who feed on the nectar and transfer pollen in starlight. Just as I am appreciating this bit of interesting knowledge the huge cacti abruptly disappear as our altitude changes and we ascend to high desert plateau. The rest of the two-hour drive passes through a seemingly endless expanse of sand, dirt, rock and sporadic clumps of sage.

Finally, the mystical red rocks of Sedona appear in the windscreen and I have reached my destination.

I am greeted by Dave, along with our dear friends, Jot, Linda and Craig, and also a tiny bodied and hugely charismatic dachshund named Olive. Her antics and affectionate cuddles go a long way to mitigating the pangs Dave and I both feel at leaving Woofus behind.

DAY TWO: SEDONA to FLAGSTAFF

“Men come and go, cities rise and fall, whole civilizations appear and disappear-the earth remains, slightly modified.” —Edward Abbey, “Desert Solitaire”

Our first stop is Meteor Crater, a mile wide and 550 feet deep. Discovered in 1891 and estimated to have been created by the impact of a single meteorite approximately 50,000 years ago, the crater is quite young in geologic time, and one of the best preserved on earth.

We approach Flagstaff through a landscape of tufted blond grass punctuated by clusters of flat red ochre rocks. In the distance, smoke from a fire that we will later find out is a prescribed burn obscures Mount Humphrey, and we can barely discern patches of white snow on its highest peak and ridgeline.

At 7,000 feet, the weather is cool in Flagstaff, and the feeling is of a Colorado mountain town. We don warm jackets and stroll around the historic downtown, including a stop at the local guitar and music shop. Surprisingly, Dave does not come away with a souvenir guitar.

We have a dinner reservation at Josephine’s Modern American Bistro, housed in a converted craftsman style residence, and it’s a good thing we do, because although it is a Monday evening, the place is jammed. A welcoming fire blazes in the stone hearth, and we enjoy a rather fancy meal (wok charred organic Scottish salmon with cranberry citrus sauce and sweet potato gnocchi for Anna; smoked pork ossobuco in Achiote demi-glace with Tillamook green chili polenta for Dave) accompanied by a crisp white Soave wine, all for about half the price the same might cost in the Bay Area. Dave wonders if housing prices too are lower here, but a quick Zillow search reveals there’s not much difference. That’s okay, we have no plans to move here. “But if you were in your twenties, might you?” Dave asks. “No,” I smile, “I’d move to Colorado.” (Which is what really happened, by the way.)

DAY THREE: FLAGSTAFF to LAKE POWELL

“There is no lack of water here unless you try to establish a city where no city should be.” —Edward Abbey, “Desert Solitaire”

Heading north, a thundercloud slaps our windshield with sleet, and Dave muses that we don’t have chains on board. No matter, for soon we are out from under the cloud. Sparse pine trees give way to stunted and even sparser bushes which give way to grasslands and eventually become a landscape of sand, rock and the occasional courageous tuft of dry grass.

Not many settlements out here, and the few small holdings we pass are broken down structures with faded signs proclaiming “FOR SALE”.

Odd mounds of surprisingly multicolored sand—pink, pearl, green, and gray—add bas relief to the flat desert floor.

The geologic drama of the landscape increases as we approach the northern rim of the Grand Canyon and our next stop, Horseshoe Bend.

A moderate walk from the parking lot leads to the viewing area, and although the temperature is only 70 degrees, there is no breeze and soon we both wish we’d worn shorts.

We are not alone on the trail, but high season tourist crowds have not yet arrived, so we have no trouble finding unobstructed views of the iconic—and aptly named—Horseshoe Bend in the Colorado river.

We stay well away from the edge, unlike some intrepid—or foolhardy—souls.

At Glen Canyon Dam we make our way to a scenic overlook by descending a stone path carved into rock that looks like undulating pink waves. Huge boulders the color of overripe persimmons line the trail, laid one atop the other at wacky angles and scored with deep parallel grooves.

Our berth for the night is the Page Lake Powell RV Campground. We cook ourselves an easy dinner of artichoke and spinach ravioli with Bolognese sauce and a green salad, and spend a reasonably comfortable night. Luckily, the temperature is cool enough that if we open the windows and turn on our fan there’s no need to run the AC. We scheduled this trip for late April-early May in hopes of avoiding extreme heat—or cold—in the desert. So far, so good.

DAY FOUR: LAKE POWELL to GOULDINGS

“Each thing in its way, when true to its own character, is equally beautiful.” —Edward Abbey, “Desert Solitaire”

At the appointed hour we join a throng of tourists waiting to board shuttle vehicles for a pre-booked tour of the Antelope Canyon. Our guide, Mariah, informs us with pride that she is 100% Navaho, born nearby. She directs our group to squeeze onto two bench seats of a four-wheel drive vehicle and we set off to on a sandy track to the entrance of the slot canyon. The short ride allows just enough time to find out our group consists of a couple from Texas, a foursome from Salt Lake City, a couple of Virginia, and a pair of newlyweds who have traveled all the way from Korea.

Mariah leads us through a narrow fissure in the rock into a luminous passage of swirling apricot and salmon-colored shapes.

We twirl in slow circles, attempting to capture in photos the wonder of delicately striated and sculpted sandstone illuminated with soft light from above.

Eventually I slide my camera into my pocket and simply gaze in awe.

No doubt about it, over the last few days, the desert has worked its magic and I have begun to fall under its spell. Where before I saw inhospitable landscape, now I glimpse beauty in the ever-shifting palette, the time-sculpted landscape, the over-arching sky. I sense why people revere this place. There is glory here, from the subtle to the dramatic, and it is not man-made.

Do we regret anything about our spontaneous decision to leave Provence two days early and return to Chablis by car? No. Not even the bumper-to-bumper traffic we encounter en route? Well, okay, next time we won’t make the mistake of traveling on the last day of a long holiday period, especially if driving north from the south of France.

Two weeks ago, spring seemed far away, but now, signs of the new season are all around us. Climbing roses brighten stone walls in the village, and tiny green leaves soften the woody vines on the hillsides.

We stay in a roomy and stylish AirBnB that comprises the top two floors of a three-story house and includes a small terrace overlooking the river. A narrow cul-de-sac lane leads to our front door, and every time we step outside Dave makes friends with a local feline.

We dine well during our short stay in Chablis: A repeat gastronomic adventure at Au Fil du Zinc, where we enjoy the chef’s inventive creations such as hay-infused (!) artichokes; petit déjeuner at a friendly art café; and an exquisitely crafted meal at Les Trois Bourgeons that almost makes up for excruciatingly slow service.

We have come back to Chablis on a quest, of course, to procure a case of wine unavailable in the US—La Chablisienne Grand Cru “Les Clos” 2019—and ship it to our home. The vintage is the ultimate distillation of time and place, reflecting when the weather began to warm that particular spring, how much rain fell during the summer, even the frequency of clouds. The cost of the wine is reasonable, the shipping too, and for a nominal additional fee we request expedited delivery, hedging our bet that the vagaries of weather and commerce will allow the wine to survive the journey unscathed.

Our quest fulfilled, we depart Chablis for Paris. It is with a sigh of relief and a thrill of anticipation that we exit the Péripherique and glimpse the Seine. As we approach our destination, we text our VRBO host, Jacques (name changed for everyone’s protection). He informs us via a series of curt, bossy texts that we MUST arrive by taxi (not rental car) because there is no street parking. We explain that we cannot arrive by taxi; we will drop Anna off with our luggage at the curb in front of the apartment. Jacques refuses to accept this plan. But we hold our ground. “Okay,” he snaps, “I will meet you.” But when we arrive, he’s not there. We wait, our rental car perched on the sidewalk—two wheels on, two wheels off—for a full 15 minutes.

Jacques finally shows up, a tall, ginger-haired man who gestures at our car and snarls, “I told you, you can’t park here!” (Seriously? If you hadn’t kept us waiting, we wouldn’t be parked here!) Such “pleasantries” aside, we quickly unload our luggage and Dave removes the offending vehicle. Jacques leads Anna up a flight of winding stairs to an apartment whose best feature is its location, a few steps from one of our favorite Paris haunts, the Place des Vosges. After warning Anna not to disturb the neighbors or accidentally lock herself out of the apartment, our haughty host retreats, never to be seen again.

Langdon has already arrived in Paris and we have arranged to meet him at Ma Bourgogne for an apératif. As soon as we sit down, “our” waiter hurries over to take our order. It is a pleasure to see him every time we visit—he is always on duty it seems, no matter what time we stop by—but his constant presence illustrates the long hours demanded by his profession. “When will you get to retire?” Anna asks. He smiles and looks skyward. “In Heaven,” he responds. His tone is light-hearted, but also hints of regret—or resignation? Note: Since the pandemic, waiters have begun demanding fewer hours, so perhaps things are changing. We notice two new young waiters hovering nearby. Waiting in the wings, perhaps.

A visit to Paris always includes pilgrimages to favorite places. Dave has been dining at the family-owned Le Villaret for over 30 years, but Langdon has never been, and it’s high time we introduced him.

More family members arrive, sleep-deprived but cheerful (one niece without her luggage, but it will show up a day later), and the marathon begins. Dave leads everyone on a long march through a maze of left bank streets starting at the Jardin de Luxembourg, proceeding to Saint Germain des Près with a brief halt at Place Furstenberg before a lunch stop at Brasserie Lipp. And that’s just for starters.

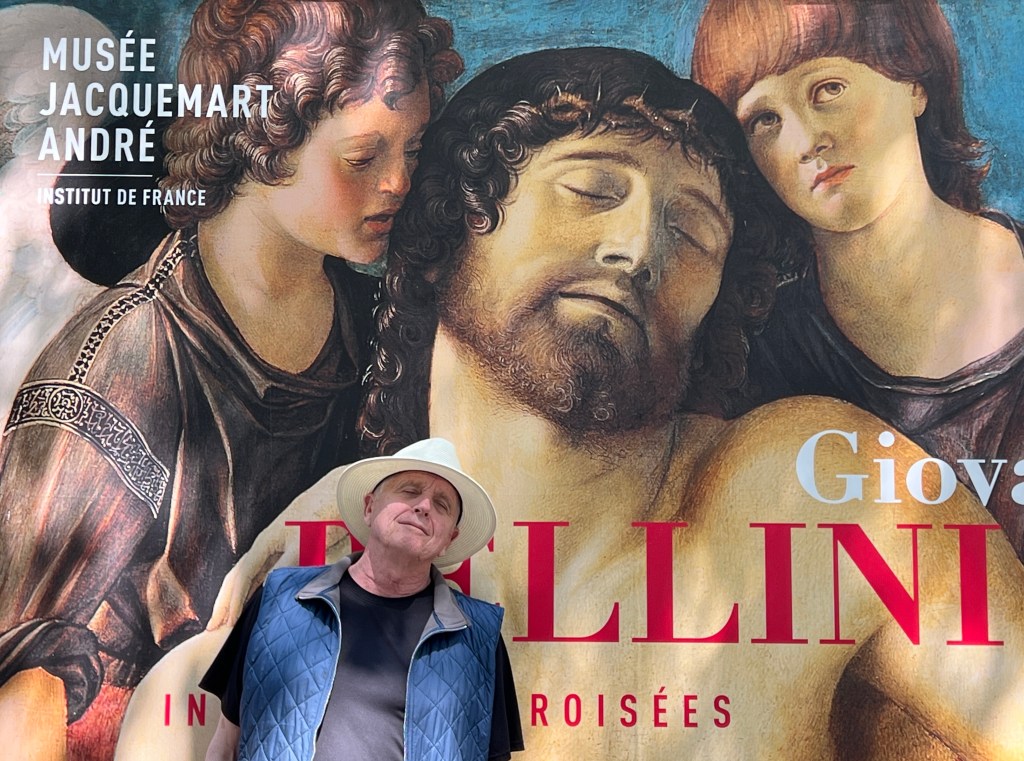

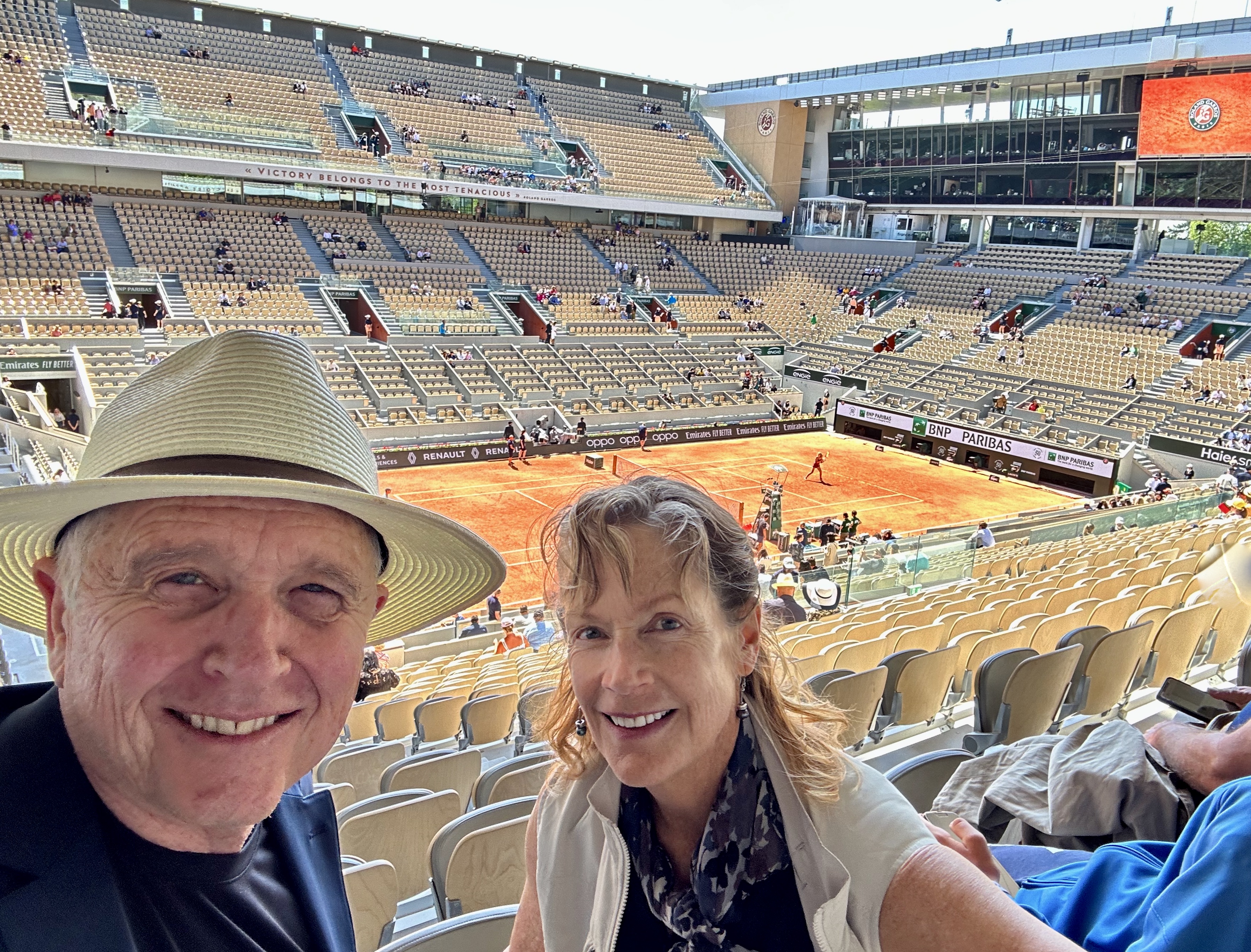

Meeting up with family and sharing the delights of Paris is a rare treat worth an infinity of Michelin stars. Each day brings new explorations and lengthy wanderings around Paris.

The best part is being together. (And the pâtisseries. And the architecture. And the cafés on every corner. And…) The worst part is missing the family members who can’t be with us. But they are in our hearts and minds.

Au revoir, Paris. See you next time!

And so our circular travels end where they began, at home. In our case, to a clean house a happy dog*. Two weeks later, a case of imported wine arrives—twelve bottles, each miraculously intact. Every sip transports us to a certain hilltop vineyard and a unique moment in time.

*It took time and effort to find a trustworthy person to stay in our home and befriend our dog in our absence. For anyone else who has a pet and/or isn’t comfortable leaving their home unoccupied, it is worth mentioning that we recommend “Trust My Pet Sitter” trustmypetsitter.com, a newish agency whose team provided outstanding service at a reasonable cost. (Not to be confused with “Trusted Housesitters”, an agency we’d used before but abandoned due to less-than-great experiences.)

On our way south from Lyon to Avignon, we stop at Vienne, once a Roman settlement (like most towns in this part of southern France) and supposedly full of interesting ruins. We park in a tree-shaded lot and set off on foot past closed shopfronts and graffiti-tagged walls to the rebuilt remains—not ruins—of a large Roman temple. A sidewalk café faces the temple, and we order two coffees. The café is quiet; only a few tables are occupied. Our waitress delivers our espressos, and just as we take our first sip, a young man bursts out of the café door and crashes through a cluster of tables, chased by a burly man with a shaved head who catches up with him and shoves him into a railing. They aim blows at each other, and for a moment it seems we could be caught up in a brawl, but then two more men race over, tackle the aggressor and pin him to the ground. He struggles, and one of the men holding him down shouts, “Tu te calmes ou je t’écrase la tête!” (Calm down or I will smash your head!) An aproned waitress puts down her tray and helps immobilize the man by sitting on his legs. A small crowd of onlookers has gathered, and someone must’ve called the police, for we soon hear the two-tone wail of approaching gendarmes. Our waitress gives a disapproving shake of her head. “Bienvenu en France,” she says. We pay our bill and leave, unwilling to witness any further drama. Such is our introduction to Vienne.

Things improve on our way back to the car. We pass a shoe store and Dave veers inside with a treasure hunter’s gleam in his eye. “I’ve been wanting some of those colorful tennis shoes I saw men wearing in Paris,” he explains. After trying on several pairs of shoes and fending off an opinionated saleswoman’s insistence that he buy a different (more boring) pair, he settles upon a pair of carrot suede shoes that fit like a dream and transform his image from tourist to trendsetter.

We follow the Rhône River valley into the heart of Provence, and it’s easy to see why so many people love this region. Red poppies and vineyards seem to line every roadside, ancient stone villages perch on hilltops and leafy sycamore trees shade the avenues. And of course, sunlight bathes the landscape. “I feel like Monet,” says Dave, as we pass yet another grassy field dotted with bright crimson flowers.

Dave has booked us a seven-night stay at Le Moulin du Four, a renovated old mill in the countryside outside Avignon. We arrive after a long day of driving and it feels like paradise: a classic old Provençal house set in a tree-shaded garden next to a flowing stream. Our apartment opens onto a terrace with table and chairs and a garden with a hammock and comfy chaises longues, and Anna is tempted to quit sightseeing and spend the next seven days right here.

Inside our apartment the temperature is perfect for a dry martini, but not for our comfort. The weather has been unseasonably cool, and the only heat source is a pellet stove in the main room (which we promptly light) but it cannot effectively take the chill off the high-ceilinged rooms and thick stone walls designed to keep heat OUT. Never mind. We wear our jackets around the house and sweaters and socks to bed. Note: Later in the week when warmer weather arrives, we will be glad of the coolness of our rooms.

We’ve chosen this Airbnb for its central location as much as for its charm, and each day we target a few places on the map and set off to explore. In the walled city of Avignon, we stroll along shaded streets and gaze in wonder at the Pope’s Palace and cathedral.

Early one morning we arrive in Gigondas and wander the narrow, cobblestoned streets before any other tourists arrive. Nestled at the foot of the Dentelles de Montmirail mountains, the tiny village is picture-perfect Provençal, and namesake of the celebrated Rhône Valley red and rosé wines produced here.

In Vaison-la-Romaine, we thread our way through the busy, “new” town and across the old Roman bridge into the medieval “old” town. Dave squeezes our car into a fortuitous parking spot and we continue on foot, passing under a stone archway where a street musician strums a guitar and sings a French ballad.

Winding our way up a continuous incline of cobbled streets and stairs, we traverse several tiny squares with a stone water fountain at their center.

Many of the old stone houses display fine architectural details.

Eventually we reach the top of the hill and the ruins of a fortified castle. During the Middle Ages, inhabitants of Vaison-la-Romaine migrated here to the relative safety of the steep rocky hilltop offering panoramic—and defensively strategic—views over the surrounding countryside.

On a day when our route leads past the town of Orange, we stop for a coffee and visit the Roman theater, the best preserved specimen of its kind in the world. The massive venue is still in use, hosting a summer opera festival and accommodating up to 9,000 spectators.

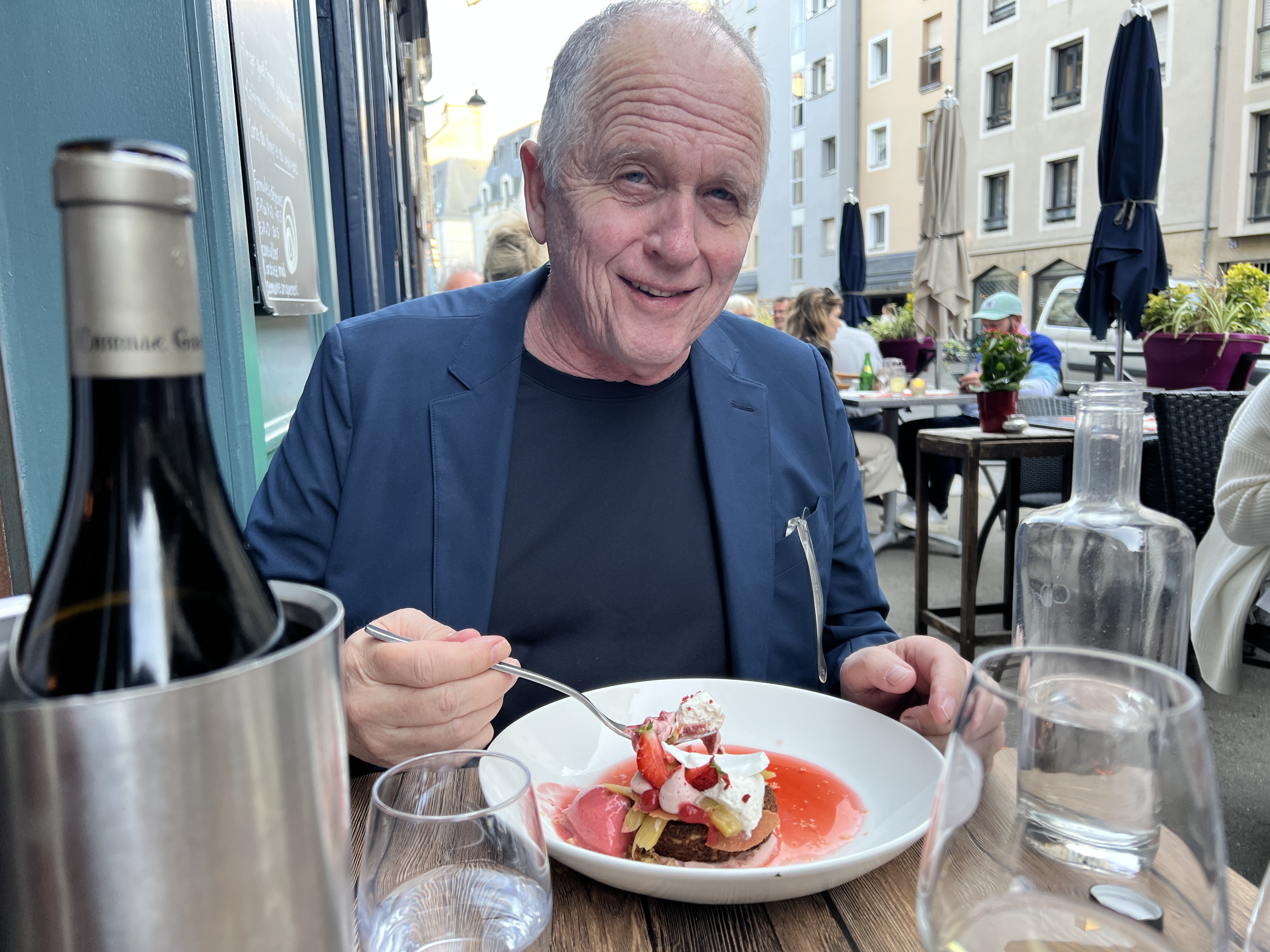

Without a doubt, the culinary highlight of our week in Provence is a multi-course meal at Le Chenet, a Michelin-starred restaurant located near the Moulin du Four. Read on for a description, or simply scroll down for the visuals. The adventure begins with an amuse-bouche of fresh garden peas and herb sorbet. Then we have choices: For Dave, tuna tartare, foie gras and ginger, followed by morel mushrooms, sautéed asparagus and roasted veal served with sa tête (a cleverly disguised way of saying veal brains, which Anna doesn’t divulge until he’s eaten most of it, commenting on its “chewy texture and nutty flavor” and wondering aloud if it is some sort of mushroom). Anna’s meal choices are squash flower soufflé and trout mousse in a balsamic reduction, followed by line-caught monkfish in an emulsion of haddock, grilled fennel and leeks. Then it is time for dessert: a pink orb glazed with strawberry gelée over a layer of feather-light strawberry cream and a core of frozen strawberry sorbet served on a praline wafer. To accompany this already sufficient morsel, a tiny dish of strawberry “caviar” topped with a wildly aromatic basil-lime sorbet. But we’re not done yet. In such an establishment, Les Mignardises (sweet treats), always follow the dessert. We have just enough room left for a thumbnail-sized cube of pistachio cake and a chocolate truffle no larger than a pea.

At this point in our travels, Anna achieves her dream of a day—or two—without sightseeing. In the morning, she hikes up a narrow canyon to the top of a ridge with a view across the river to Avignon and the distant Mount Ventoux. At midday, she handwashes clothes and hangs them on the line to dry. Isabelle, our Airbnb hostess, is also in the garden, and they enjoy a friendly chat. Later, Anna sits at the table on the terrace and makes use of the art supplies she brought all the way from California. She hears the sounds of birdsong, of pencil on paper, of flowing water.

Meanwhile, Dave sets out on a solo mission to Isle-sur-la-Sorge and Bonnieux, with drive-by nods to Lacoste and Menerbes.

It is not the first time he has been to these towns; he visited often in the autumn of 1993, when he and his family spent a month in a sprawling old farmhouse in the hills above Apt. He has fond memories of shopping at local markets and plucking a freshly slaughtered turkey to roast for Thanksgiving dinner.

At a café stop in Bonnieux, he greatly impresses the barman and his cronies who mistake him for Anthony Hopkins.

Before returning to our mill house from his solo travel day, Dave stops to pick up provisions at the local grocery. The shop is excellent (Isabelle tells us that people drive all the way from Avignon to shop here), and since many restaurants are closed due to the Ascension holiday, the next two nights we cook for ourselves and dine informally—and more simply—in the garden.

During one such dinner, as we enjoy a bottle of Chablis from our dwindling supply, Dave is struck by a possibility: Why not return to Chablis for two nights, buy a case of our favorite (La Chablisienne 2019 Grand Cru “Les Clos”) and have it shipped to ourselves in the USA? Why not, indeed? We’d have to depart Provence two days earlier than planned, drop our rental car in Paris instead of Avignon, and trade a three-and-a-half-hour ride on the TGV (Train de Grande Vitesse, ie. High Speed Train) for a five-and-a-half-hour drive to Chablis. For us, it’s a no-brainer. As much as we love the peaceful setting of the Moulin du Four, we have had enough of Provence, and it is an easy matter to alert Isabelle of our early departure, cancel our train tickets and book an Airbnb in Chablis. And so once again, we swerve from our original itinerary and follow a spontaneous déviation.

On what has turned out to be our last day in Provence, we visit a place neither of us has been before: the startlingly beautiful and impressively preserved town of Uzès. Every elegant façade and even the paving stones are fashioned from creamy white limestone, lending a remarkable harmony and grace to this “city of art and history”.

We lunch at a café on the main market square in Uzès, La Place-aux-Herbes, and then head for the grand finale of our time in Provence, the ever-astounding Pont du Gard.

This remnant of Roman engineering—constructed without mortar, BTW—never fails to amaze. Anna can’t help but wonder if the people who designed and built it (most of whom were enslaved laborers) ever gave a thought as to whether or not it would still be standing more than 2,000 years later.

In anticipation of the drive to Chablis, our car—especially the bug-spattered windshield—needs a serious scrubbing. We find a lavomatique automobile, make our choice from a long, semi-comprehensible menu of cleanliness options, and then stand back to watch the show. (In automatic car washes in France, driver and passengers must exit their vehicle before the mechanized process can begin.) Fifteen minutes later, we come away with a gleaming car and an expanded vocabulary that we might, or might not, ever utilize again. (Who knew that pulverisation is the French word for “spray”?)

Our next unforseen adventure awaits on the road to Chablis, but we will save it for the next post!

We hadn’t originally planned to spend time in Lyon; we were going to spend three days hiking in the Alps. But wintry weather makes us think again. We worry that hiking will require snowshoes, and clouds will obscure the mountain views we were hoping to see. So, during dinner one evening in Burgundy, we hatch a new plan. Luckily, Dave has the foresight to always book places that allow penalty-free cancellations up to 24 hours in advance, and he enjoys the challenge of finding new and interesting places for us to stay, so in short order he has cancelled our alpine reservation and replaced it with three nights on an island in Lyon. But first we visit Pérouges, a walled village dating from around the 9th century and built with a mind-boggling number of individual stones.

Strategically located on the road from Lyon to Geneva, the village flourished through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, becoming an important textile center known for the craft of its weavers.

Its fortunes dwindled in the 18th century, when a new road was built that bypassed the village, and new weaving techniques were developed using large, industrial sized looms.

At its height, the population of Pérouges numbered about 1,000 souls, but by the early 1900’s, businesses had shuttered, walls crumbled, and no more than 10 or 20 people remained. Structures were plundered for building materials to use elsewhere.

In 1911, horrified by the prospect of this historic jewel of a village being destroyed, a group of concerned citizens formed an association whose members each bought a house in Pérouges and rebuilt it. The association grew, and house by house, the village was restored. Today it is living replica of a medieval village, all signs of the modern world hidden from view, inhabited by artisans and tradespeople.

We arrive in Lyon in the late afternoon. Built on forested hills around the confluence of the Saône and Rhone rivers, Lyon and its environs impress us as a vibrant and attractive place to live.

Besides being considered the capital of French gastronomy, it is one of the largest metropolises in France, and the second most important business center (after Paris), with numerous regional headquarters and financial institutions.

Our rental apartment is on L’Île Barbe (or Insula Barbarica—the wild island), in the middle of the metropolis, but a world apart. Once a site of druid worship, in the 5th century the island became the site of one of the earliest Christian monasteries in France. Endowed with a wondrous library by King Charlemagne, the abbey withstood attacks by Saracens and Protestants in the 1500’s, became a facility for elderly or infirm priests in 1741, and was finally sold and dispersed during the French Revolution. Today, except for a small public park and playground, the island is private, the land and buildings owned by a small community of residents. The vestiges of its long and tumultuous history are reflected in the architectural mash-up of ancient ruins, medieval remnants, and subtle modernization, all blending into an enchanted hodge-podge of a place lost in time.

To reach our accommodation we make our way across a rickety, single-lane bridge (more often used by cyclists and pedestrians than cars), enter a code that unlocks an ornate iron gate and turn into a narrow lane that leads past the remains of a long-ago cloister.

Our host Bénédicte is a cheerful, outgoing young woman whose family has lived on L’Île Barbe for five generations. We follow her up a winding staircase and she explains that the building, once a monk’s refectory, was used by her ancestors to store junk. She recounts how she and her brothers had to clear out three stories of dusty rooms crammed floor to ceiling with centuries of cast-off furniture, art, textiles, books and memorabilia in order to create three holiday rental suites.

Bénédicte leads us into our top floor suite through a small foyer and tall, mirror-paned doors into a cavernous main room. The luxurious sitting area, dining table, kitchenette and doors leading to a small terrace are definitely more space than we need, but it is the only room available, the price is reasonable, so here we are, and we aren’t complaining. (Also, the internet is reliable and fast.)

Palladian windows look down onto a peaceful garden where remnants of the Romanesque abbey church are still visible: a ghostly archway embedded in the wall of a converted cottage; a subterranean entrance to an ancient crypt; and an interior wall of the abbey church, now an exterior façade.

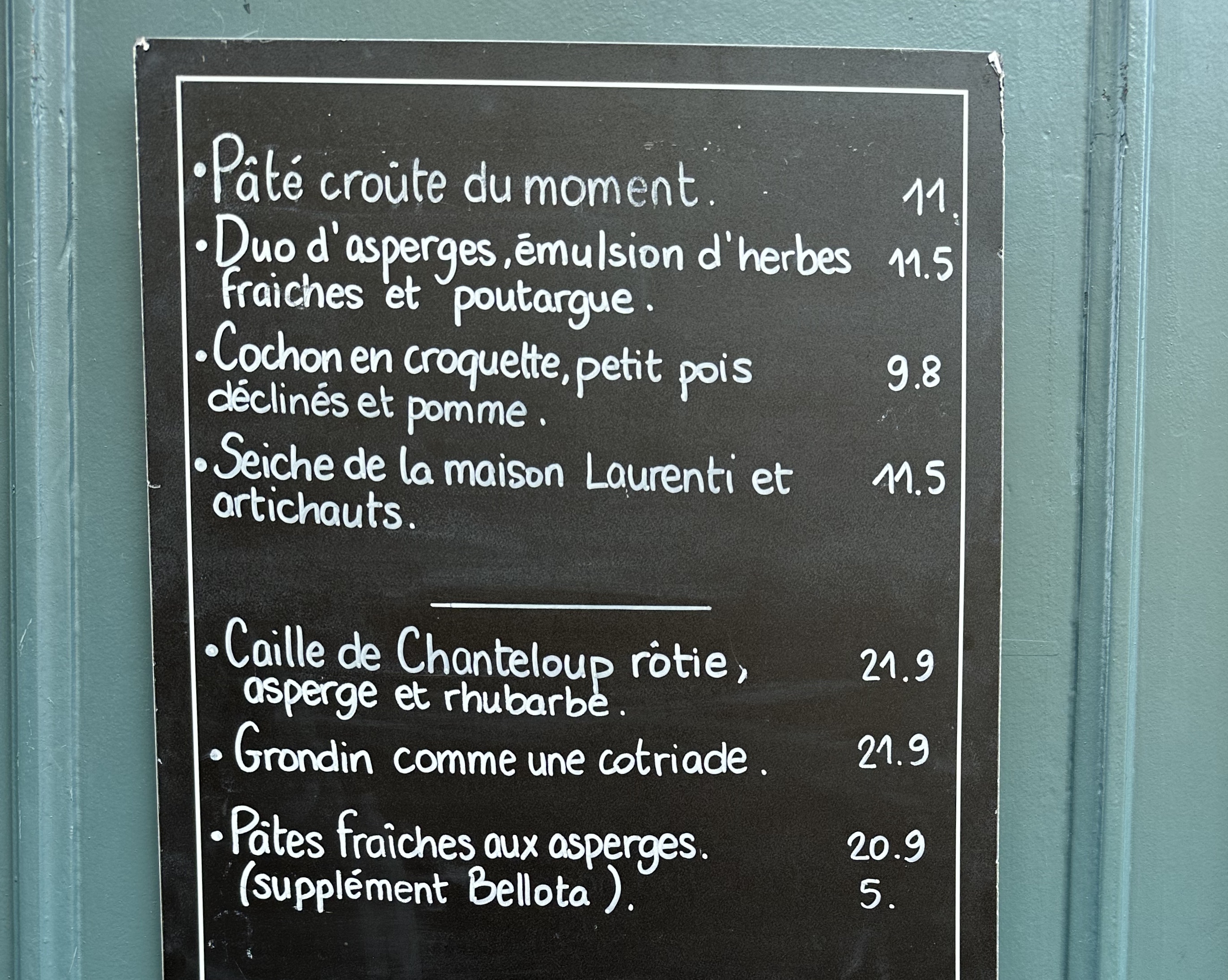

It’s time for our first meal in Lyon, fabled foodie’s paradise. We walk across the river to Pistou, a nearby restaurant recommended by Bénédicte, and enjoy a meal so delicious that we wish we could return every evening of our stay. Unfortunately, the staff is going on a week’s holiday the next day, so the best we can do is count ourselves lucky we managed to catch one meal here. Dave swears that his entrée is the freshest, most refined tuna tartare and vinegar-infused rice he has ever experienced (and that is saying A LOT), and Anna can’t help but exclaim over the burst of flavor with every bite of her cod, white asparagus and nutty cereal risotto bathed in frothy caviar sauce. So far, so good on the gastrono-meter.

There are no shops or restaurants on the island, so the next morning we make the short journey across the bridge to the nearest bakery, a fragrant, bustling establishment offering not only a vast selection of baguettes but also an array of tartes, brioches, croissants, sandwiches—in short, any breakfast pastry or picnic fixings our hearts might desire. We stock up while we can; the bakery will be closed for the next two days.

A brief note about opening—and closing—hours in France: In Paris, one can always find an open bakery, shop or restaurant, but in provincial towns and villages, even a big city like Lyon, opening days and times are sporadic, and sometimes seem downright capricious. Advance planning is essential, unless one enjoys running out of milk and skipping meals.

We set out to explore the Old Town of Lyon, but after twenty minutes of shouldering our way through swarms of chattering teens, tourists, extended families and baby carriages, we realize that Sunday afternoon on a three-day weekend (which most French will stretch to four days, and some simply taking the entire week off) is probably not the best time for a relaxed stroll around narrow winding streets.

About holidays in France: The French are notorious for “bridging the gap” between weekends and holidays, and because Wednesday, May 1 is French Labor Day, Wednesday, May 8 is VE day, May 9 is the religious Ascension Day holiday and businesses are closed anyway Sunday, Monday and/or Tuesday, many people simply take the first two weeks of May off. We admire the French sense of work-life balance, but traveler be aware.

To escape the crowds, Dave retreats to The Smoking Dog Pub for a beer. To his delight, he finds a cold IPA and a Sunday afternoon playlist of All Beatles All The Time. Anna hikes to the top of the nearest mountain and finds views more reminiscent of Italy than France.

A visit to Lyon would be incomplete without a meal in at least one of the seven (7!) Paul Bocuse restaurants scattered around the city. (Who is Paul Bocuse? He is one of the founding fathers of French nouvelle cuisine, aka the Pope of French Gastronomy.) Each of his Lyon restaurants offers a different atmosphere and menu, and the largest, the casual Brasserie L’Ouest, is very convenient to where we are staying. It is a SCENE. At least five different wait-staff attend our table, and the restaurant is filled to the brim with families, couples and friends. Dave orders a classic steak tartare avec frîtes and salad, while Anna enjoys a three-layer concoction of rice, marinated beets and seared salmon in a light sorrel sauce.

Instead of ordering Chablis to accompany our meal, we decide to try a half-carafe of white wine from southern Burgundy. (What were we thinking? Henceforth we will come to our senses and return to drinking Chablis.) The backdrop of our meal is the constant back-and-forth of service and a large open kitchen where cooks wearing tall white chef’s hats scurry between stations. The head chef communicates with his minions via microphone and his instructions are audible to the entire restaurant. It is not an intimate dining experience, but it is definitely entertaining, and not to be missed.

In the part of town known as La Croix Rousse, formerly a silk weavers district, we make sure to visit the huge trompe l’oeil painting that creates a 3D illusion of neighborhood dwellings, shops and street life on what is actually a large expanse of blank plaster wall.

After each sojourn across the water into town, we are happy to leave busy city streets behind and return to our island refuge. Intriguingly, a high, locked gate blocks entry to the other end of the island. Anna attempts some iPhone espionage, but what lies beyond remains a mystery.

Two great meals, one to go. On our last night in Lyon, we find a friendly restaurant and a menu with unusual and delicious choices at Copains Copines sur la Colline (Friends on the Hill), a small “bistronomique” restaurant in the Croix Rousse district. Anna orders an entrée of tandoori chicken breast with onions, cucumber, coriander with raïta sauce topped with a teaspoonful of coconut curry sorbet. Her main course is steamed yellow monkfish with wok-fried vegetables served over ramen noodles and drizzled with a light coconut-lemongrass-coriander sauce. Dave orders a main course and a dessert: Truffle risotto with ham, parmesan and hazelnuts, followed by mojito sorbet with morsels of buttery pound cake and mint sauce.

And so ends our time in Lyon. If our short visit is any indication, the appellation “gastronomic capital” is true.

Five days in, and we have recovered a few IQ points lost to jet lag, though most mornings, our brains still feel smothered in cotton wool. Could it be the wine? Surely not.

The day we depart Chablis, we rendez-vous for lunch with Anna’s brother Lon and his friend Kate, who also happen to be in France. The four of us enjoy a leisurely meal and are very pleased indeed to share time together in France. After coffee and dessert, we go our separate ways and as soon as we get a few miles down the road, we kick ourselves for not taking a photo of our reunion. For the record, we met in the village of Collanges-la-Vineuse, southwest of Chablis in an area of tree-lined roads, vine-covered fields, and the occasional cherry orchard.

We continue southeast into the region known as La Côte d’Or (golden hillsides). Repeating patterns of vines cover the hilly green terrain like patchwork. Red tile-roofed houses cluster around tall church steeples. The soil changes from the pale chalky clay of Chablis to a loamy dark caramel. Lilac blossoms—white, lavender and deep purple—seem to decorate every roadside hedge and garden. In one tiny village we come upon a collection of antique chauffrettes (metals pots that are filled with slow-burning paraffin to keep the vines warm against frost), arrayed on top of an old stone wall.

Our destination is Domaine des Volets Bleues in Orches, a rental house in a secluded hamlet consisting of about a dozen dwellings tucked into the lee of a steep cliff. We will stay here five nights, per Anna’s request for this trip to be less peripatetic than previous travels, and we are both looking forward to staying in one place and embarking on day trips to explore the region.

A narrow lane with a steep hairpin turn leads to the house. Uncertain where we should park, we stash our car around the corner a few meters away and walk to the front door. As we approach, a short, wiry woman with close-cropped grey hair steps into the road, draws a quick puff off her cigarette and tosses it to the ground. She grinds the cigarette butt with her foot and barks, “Where did you park your car?” We presume she is our host, despite the lack of friendly preamble. (No “Hi, you must be Dave and Anna?” Not even a “hello”?)

Never mind. As soon as we follow her into the flagstone-floored entry, the brusque greeting hardly matters. The house dates from the 16th century, and has been carefully renovated to retain period details such as exposed stone walls and soaring ceilings supported with beams the size of entire oak tree trunks. Modern conveniences have been thoughtfully added: well-appointed kitchen and bathrooms, a washer/dryer and super-fast internet. Furnishings and décor are artfully curated and convey a comfortable yet stylish “lived-in” feel; it is obviously someone’s home, not just a rental unit.

Our host gives us a quick tour, thawing only slightly when she realizes that we are not strangers to France (or to England, where she is from) and so she won’t have to explain all the basic ins and outs of local culture (such as shops closing for lunch and restaurants often closing on Mondays). We soon discover that she is not the owner of the house, but the property manager, who, along with her husband, oversees about 24 properties. (Thus explains—sort of—her gruff welcome.)

The owner of the house, Alex Gambal, is an American who moved to France with his family 30 years ago to become a winemaker. He has written a book recounting his experiences, “Climbing the Vines in Burgundy” and has left a copy for us to browse. The book could use some editing, Dave says, but is nevertheless a fascinating read.

We wake up our first morning at Domaine des Volets Bleues to find the internet down due to a system-wide network outage. A weak phone signal means tethering to our phones is not a viable option, and First World Problems ensue: We can’t read the New York Times, send or receive emails, edit photos that upload to the cloud, research our sightseeing plans or even check the weather forecast. Anna can’t post to her blog or attend her British Book Club via Zoom. However, we are still on holiday in France, so it’s not all bad. Besides, internet outages are usually sorted within a few hours, right? (Wrong. Spoiler alert: We remain offline until we depart, four days later. This is unexpected, and a bit inconvenient, but it does not dim our appreciation for the lovely house and region. And, we remind ourselves, one of the requirements of travel is a willingness to cope with the unforeseen.)

We head to Beaune, a prosperous town known as the epicenter of Burgundy wine, park the car and explore the old town on foot. The famous Hospices de Beaune with its magnificent Burgundian tile roof lives up to the hype of its being a masterpiece of medieval architecture. Founded in 1443 as a hospital for the poor and orphaned, the hospital remained in continuous use through World War I, when the nuns cared for injured servicemen.

While in Beaune, we enjoy a delicious bistro lunch of seared tuna salad (Anna) and steak tartare avec frîtes for Dave.

Another day, we have booked a “tasting workshop” at Dufouleur Frères in Nuits-Saint-Georges. At the appointed hour we drive through the gate and meet our energetic young host, Jean Dufouleur, one of the many cousins descended from generations of winemakers. The family name—Dufouleur—he informs us, comes from the word for a person who stomps on the grapes to make wine—un fouleur—grape crusher. We learn how he came to be an oenologist—a scientist of wine and winemaking—and about his vision of an environmentally-sustainable future for his family’s winery. On a large map, Jean points out the region’s different vineyard plots (called climats), and explains that white Burgundy wines depend as much on the producer’s methods and intentions than a given terroir. Dave is familiar with various winemaking techniques, but Anna is interested to learn that while terroir supplies the raw materials, the élevage (aging and finishings processes) can make—or break—great wine.

Most mornings, Dave finds a new boulangerie (bakery) to sample, and we manage to squeeze in at least one more wine tasting.

One lunchtime, Dave is tempted by a restaurant whose menu lists about 15 varieties of pizza. “I’d love a pizza”, he says. Anna has her doubts, but the menu also offers a couple of salads, and so she agrees to give it a go. The look on Dave’s face says it all: pizza, like many things, is different in France.

It might seem like all we are doing in France is eating and drinking, but we also spend plenty of time exploring, on foot and by automobile.

Obviously, we spend a bit of time making photos. Dave prefers the challenge of composing landscape shots; Anna is drawn to details.

Finally it’s time for the “Anna Roots Tour”. She has fond memories of living in a large apartment above the stable block of the Chateau Dracy-les-Couches, preparing a fleet of bicycles and getting to know her fellow bike tour guides. She has always thought she might visit again someday. But on this cold, rainy afternoon 35 years later, the place only looks vaguely familiar, and Anna feels no nostalgia, rather a sense of contentment to have “been there, done that”, and to now be in a different place and time of life.

On our last evening before departing our blue-shuttered domain, we dine at Le Bistrot des Falaises (the cliffs bistro), in the nearby hamlet of Saint Romain. Our meal is a revelation of fresh seasonal ingredients and inventive combinations. Anna chooses an Entrée + Plat of herring, beet and radish salad, followed by grilled octopus and braised endive in a reduction sauce. For Dave, Plat + Dessert: steak tartare and garlic roast potatoes, followed by rhubarb tart in an almond crust, garnished with a cream sorbet.

The next morning, we wake to the sound of a cuckoo calling. It is a rare and charming sound, a gentle reminder that it’s time to pack up and move on to a new destination. (Hopefully with internet access.) We’re going to stay three nights in the capital French gastronomy, Lyon. Will it live up to its reputation, and will our stomachs be up to the task of finding out?

Anyone who knows Dave will probably know that his favorite white wine is French Chablis, a succulent marriage of flinty citrus and floral notes that is made with 100% Chardonnay grapes, but is miles away, geographically and stylistically, from bold, buttery Napa Valley Chardonnay.

Terroir (soil, climate, topography) matters. The chalky soil, cool, wet climate and an aging process that takes place primarily in steel tanks is the alchemy that creates the uniquely refreshing yet complex Chablis wine.

Despite Dave’s reverence for Chablis wine, he has never made the pilgrimage to the place from which it takes its name—until now. The small, unpretentious town is something of a hidden treasure, quiet streets lined with well-kept stone houses and shops, at least two world-class restaurants, a tempting selection of wine tasting rooms, and not a tee shirt or souvenir shop in sight.

With his usual care for location, comfort and charm, Dave has booked us a cottage on the river, aptly named Riverside Lodge. Our hosts are a British couple; Julia, formerly a chef of some renown, and John, a sommelier by trade who is also an accomplished musician. The Chablis region had been their vacation destination for many years before they decided to retire and move here full time. They spent four years transforming a run-down residence, abandoned outbuildings, and wasteland of concrete and weeds into a peaceful home, a guest cottage and garden.

John accomplished most of the building work by himself (a book of photos in our cottage attests to his ambitious feat) while Julia oversaw the tasteful interior furnishings and decoration. She equipped the spotless kitchen with items that Anna always wishes to find at rented accommodation but usually doesn’t: tongs, sharp knives that actually slice, poultry shears, an adequate selection of pans, dishes and glassware, and useful condiments such as oil, lemon juice and spices.

After settling in, we join John and Julia for a glass of “village” Chablis (ie. not a Grand or a Premier Cru). The supposedly “ordinary” wine nevertheless epitomizes the characteristic freshness and mineral-infused flavors that we love, and that are characteristic of wines made here. We note the vintner and the vintage (2022 Raoul Gautherin & Fils) and resolve to buy a few bottles before departing Chablis. Between appreciative sips, we chat with John and Julia about their life here, about where they lived in England (not far from us), and about music, inspiring John and Dave to perform an impromptu duet on piano and guitar of Elton John’s “Your Song”.

A short walk across a stone bridge leads us into town and to Au Fil du Zinc restaurant, a bright, elegant room situated in an ancient mill looking out over the river. It is the sort of place where diners can choose between either a 5 or 7 course meal, with or without wine pairings. We choose the 5-course option with pairings. Describing our dining experience in words hardly does justice to the precise and inventive combinations of flavor and texture of the Japanese-influenced cuisine. But we’re going to do it anyway. To start, we are served three bite-sized amuse-bouches: scallop sashimi, escargot puffs, and—our favorite—sorrel infused purée topped with a raw quail egg nestled in a curl of carrot ribbon.

Next, white asparagus spears poke out from a bed of green pea, coconut and wild garlic mousse. This course is paired with a 2021 1ère cru Chablis, which, unexpectedly, tastes rather pallid compared to the more “everyday” Chablis poured with the appetizers. Our sommelier explains that 2021 was a tricky year, with early frosts destroying much of the harvest. No matter, we are ready to move on to our next course: seared Shiitake mushroom vélouté garnished with Shiso leaf and a chewy dollop of black pudding.

Course portions are petit and we still have room for the penultimate offering: a tender filet of local brook trout layered atop slivered rhubarb, green beans and almonds dressed with warm miso sauce. A forgettable red wine accompanies this course. Perhaps we would’ve been better off simply ordering a bottle of Chablis to go with our meal, but the joy is in the discovery, and besides, by now we have become friendly with our sommelier—a young Frenchman who has spent quite a bit of time in San Francisco, and surprisingly, Petaluma. When it’s time for the last course, Dave warns him, “My wife doesn’t eat dessert.” He replies without missing a beat, “That’s good, neither does our chef.” Indeed, a light concoction of fresh Provençal strawberries, crème sorbet, wafer-thin almond galette and citrus-herb marinade leaves us sated but not stuffed. We shake hands with our sommelier and walk home in the lilac-scented night.

The next day is market day in Chablis. We stroll up the main street past stalls selling local honey, rounds of fragrant cheese and charcuterie, fresh strawberries, several varieties of apples, pullover sweaters and summer dresses (wishful thinking, because the weather is unseasonably cold and cloudy). Dave stops to try on a jaunty straw hat. It suits him, and he buys it on the spot. The bearded merchant smiles. “Perhaps a straw hat will bring us sunshine,” he remarks, handing Dave his change.

Purchases at several more stalls supply us with provisions for dinner: a roasted game hen, a pint of waxy, golden potatoes soaked in drippings, fresh leeks, ripe tomatoes, and a small bushel of spinach.

For lunch, we have a reservation at “Chablis Wine Not”, a bustling, trendy wine bar we never would’ve gotten into without booking ahead. The menu offers a selection of small plates and we share a raw squid and radish salad, turkey-pistachio terrine, cauliflower tempura, and trout sashimi with seaweed crisps.

Wine enthusiasts will understand the thrill of what we do next: We drive to the top of an east-facing slope, park the car and walk through a grove of pine trees to the oldest—and most esteemed—vineyards in Chablis. No walls or fences contain us; we are standing amongst the vines. Dave gazes around in awe. “It all comes from right here!”

The mix of limestone, clay, cool climate and exposure to rain and sun on these hillsides is ideal for making great wine, even in difficult years. Cistercian monks made wine in this area as early as the 12th century, and since 1938 the wine produced from grapes grown on these 260 hilly acres—a scant 2% of Chablis vineyards—has officially been classified as Grand Cru. (It is important to note that in Chablis, Grand Cru outranks 1ère Cru, the opposite of the rating system used in Bordeaux. Not trying to be confusing, promise.) The specific vineyard names are unknown to Anna, but Dave recognizes them all: Blanchots, Preuses, Bougros, Grenouilles, Valmur, Vaudésir and—the oldest, and arguably the most venerated—Les Clos.

By now Dave has a mighty thirst, and it will only be quenched by sampling some legendary Chablis. We head back into town to La Chablisienne, a well-known local wine cooperative, and are treated to a free dégustation (tasting) of several Grands Crus. Needless to say, we come away with a few bottles. (Stocking up for the rest of our time in France—we still have several weeks ahead, and we depart Chablis tomorrow!)

In the evening, we spend a peaceful hour sitting outside on our private terrace overlooking the river. Pale pink clematis flowers climb across picket fencing and white lilac scents the air. Church bells sound from across the water. If we had any expectations about Chablis, they have been exceeded. We booked two nights here, but could’ve stayed a week.

Next we will travel deeper into the Burgundy region, an area we have both visited before, and where, 35 years ago, Anna worked as a tour leader for a small bike tour company. How much will seem familiar, all these years later? Will the nostalgia of visiting familiar places be as compelling as the excitement of new discoveries?

Then we arrive in Paris, and the answer is clear: As our location shifts, so does our perspective. We find ourselves in a perpetual state of “beginner’s mind”, experiencing everything as if for the first time. Even though we’ve visited countless times before, everything feels new, and we feel more alive (albeit minus a few IQ points, thanks to jet lag).

We check into our hotel, stash our luggage, and step outside to wander the cobblestoned streets of Montmartre. The non-stop sensory input is like a jolt of electricity that jump-starts our sleep-deprived brains.

Scooters zip past, narrowly missing car fenders and heedless cyclists. Cafés and restaurants overflow onto the sidewalks. Dogs of all shapes and sizes (a surprising number of them off-leash) trot obediently beside their humans. Bewildered tourists stand on street corners staring down at their phones. A police siren bleats a dissonant Doppler-bending wail.

A brisk hike up the countless stairs to Sacré Coeur brings our legs and lungs back online.

To my relief, the lilting intonation of native French all around us unlocks the dusty mental closet where fully formed sentences and obscure vocabulary words have apparently been waiting to spring forth as needed. How odd that these semi-intelligible sounds function as language, but what a blessing to understand and be understood.

We manage to stay awake for an early dinner of mussels and frîtes (French fries) for Anna; oysters, frîtes, and a simple green salad of the ilk found only in Paris for Dave. To celebrate our first night here, we raise a glass of effervescent Billecart Salmon (rosé) champagne. On our way back to the hotel, we pass the Moulin Rouge windmill, a familiar (“not anymore!”) landmark that is looking rather unfamiliar since mysteriously losing its arms the day before. (Probably Inspector Clouseau is on the case.)

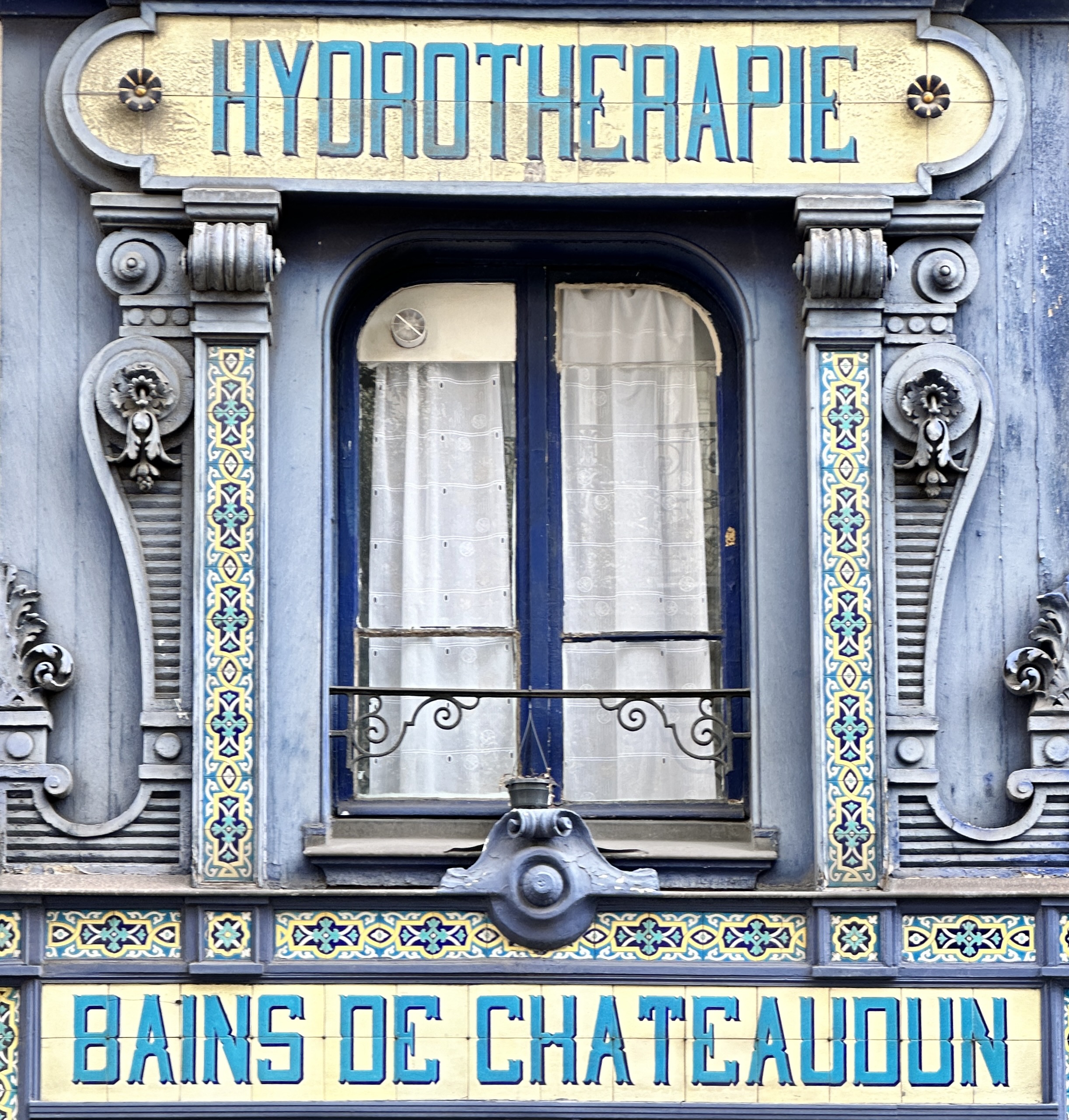

The following day will be our last in Paris until we return for a week at the end of our trip. We decide to spend part of it learning about the history of French architecture at an exhibition currently on view at the Cité de L’Architecture et du Patrimoine. Unexpectedly, much of the exhibition consists of floor-to-ceiling reproductions of Romanesque pillars, statues and doorways. Luckily, our tickets also grant us entry to a fascinating exhibit about the construction of the Paris metro system, a poignantly expressive mural showing the damage to Notre Dame after the April 2019 fire, and scenic views of the nearby Eiffel Tower.

We have booked a lunch reservation at Ardent, a newish restaurant that features grilled dishes made with fresh seasonal ingredients. Unprepossessing from the outside, perhaps, but deliciously surprising inside. We thoroughly enjoy our lunch of smokey marinated artichoke hearts garnished with caper sherbet, bacon-wrapped turbot and charred endive (for Anna); and “crying tiger” (spicy Thai marinated beef), carrots vinaigrette, roasted herb-infused veal, pearl potatoes and root vegetables (for Dave).

At the Arc de Triomphe, we cannot resist resting on a bench and watching the never-ending spectacle of traffic zooming around the giant whirlpool of the étoile. Also, our legs and feet are tired. And so we sit for awhile, mesmerized by the continuous flow of cars, motorcycles, busses, scooters and cyclists all jockeying for position as they merge from 12 grand avenues into the circular flow of traffic. We witness several narrowly missed collisions and then hear a loud thump and the sound of scraping metal. Traffic slows, and Dave jumps up to see what happened, but an instant later the frenetic pace has already resumed. He returns to our bench and fondly recounts his 1977 solo drive through Paris in his dad’s new Mercedes, navigating with a paper map spread across his lap and somehow making it around the étoile without a scratch. He laments that we haven’t rented a car or a scooter to experience the wild ride again. But there is a workaround. A few blocks away we hail an obliging Uber driver who barges into the mêlée of the étoile as easily as pulling into a parking lot. He threads his way through the throng of vehicles with alternate bursts of speed and slamming of brakes and eventually delivers us safely to the other side.

In the evening, we scour the immediate neighborhood around our hotel for the sort of brasserie we like: not too modern, not too crowded, not too brightly lit. Eventually we come upon Le Sancerre, where we enjoy a casual dinner of croque monsieur (ham and swiss melted on hearty bread) for Dave, and seared salmon (or mi-cuit, as they say here) with a side of frîtes for Anna. Dave will return to the same café the next morning for breakfast and then we’ll head to Chablis, white wine Mecca for those of us who revere crisp, mineral-driven Chardonnay.

Our trip is bookended at the start and finish by a week-long stay in a familiar, well-loved place: Paris on the front end, and now, as our travels draw to a close, the English countryside where we used to live.

We find roses at every turn, the only real thorn being the wistful nostalgia we feel that we no longer live here.

Rose: En route to our final destination, we revisit some of our favorite haunts in the Cotswolds. (Snowshill, Upper Slaughter, Lower Slaughter, Broadway, and the Daylesford Cafe near Kingham, to name a few.)

Rose: Being welcomed at the front door with a glass of champagne when we check in for a one night’s stay at the magnificent—yet intimate—Abbots Grange.

Rose: Our ground floor suite is cool and comfortable, stocked with every amenity, and conveniently located near the honor bar. Dave’s booking choices continue to impress!

Rose: Five nights at “Tyringham Small”, a converted barn adjoining the 17th century Tyringham Hall, in the village of Cuddington. Dave has done it again; the AirBnB he has booked for the last week of our trip surpasses the standard he already surpassed!

Rose: Reunion dinner with friends in “our” village, and it’s as if we never left.

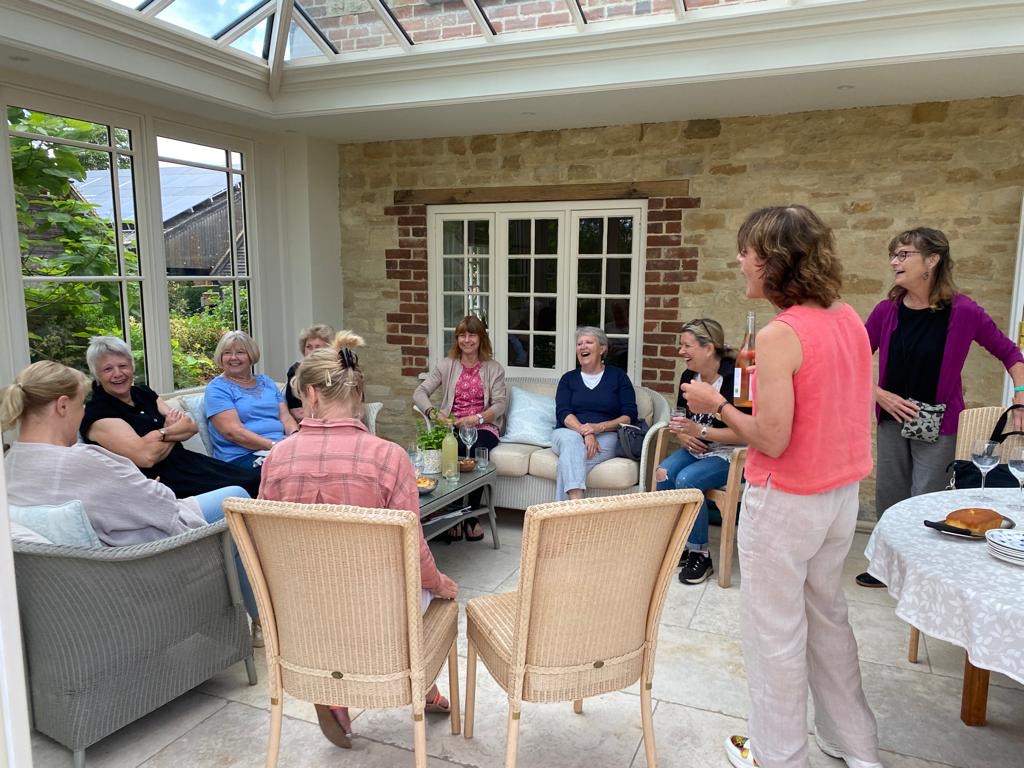

Rose: For Anna, attending a village Book Club meeting in-person instead of via Zoom.

Rose: A cosy, delicious dinner and catch-up with friends at the Sir Charles Napier, a favorite restaurant.

Rose: A day of tennis (and champagne) at Boodles, a grass court “warm-up” tournament before Wimbledon.

Rose: Sunday morning walk, coffee and cake with friends.

Rose: A last afternoon in the village, visiting with as many old friends as possible.

Rose: For Dave, a pint and a chat with the vocalist and the drummer from his fabulous British band, “Innocent Bystander”.

And now it’s time to pack our bags and take our leave, though in our hearts, a part of us always remains.

“And we ourselves shall be loved for a while and forgotten. But the love will have been enough.” —Thornton Wilder, from The Bridge at San Luis Rey

Rose: The wild beauty of Wales speaks for itself.

Rose: A three-night stay in a cottage in Capel Curig, a few miles outside of Betws-y-Coed, ground zero for hikers, climbers, campers and sightseers in Snowdonia National Park.

Rose: Dinner out at a friendly local pub called Tyn-y-Coed.

Rose and Thorn: Our townhouse in Crickhowell is stylish and comfortable, but it turns out to be only a few steps from a busy roadway. We become aware of this fact only after we go to bed and are kept awake by the din of passing lorries.

Rose: Lots of lovely footpaths and places to walk.

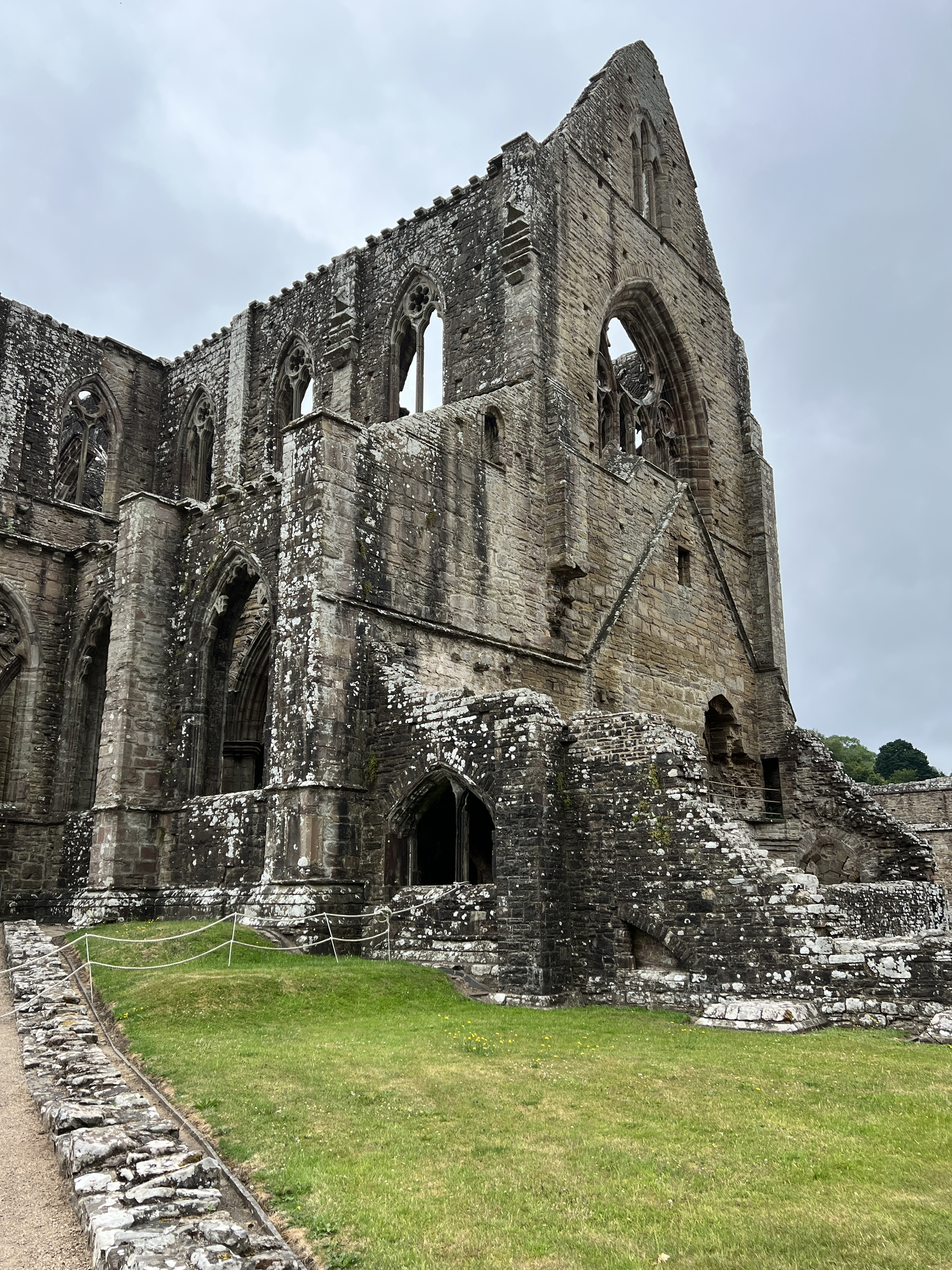

Rose: Pilgrimage to Tinturn Abbey, in memory of Lowell, who loved visiting here. Scaffolding and fencing blocks large sections of the ruins, but the setting, in a wooded, isolated valley, and the magnificent remains still stir the soul and the imagination.

Rose: The road beckons us ever onward, especially since we have saved the best for last: we will spend the final 5 days of our 5 week trip visiting people and places we know and love.

Our route takes us southwest, through scenic hills and valleys (a.k.a. “dales”), picturesque villages and market towns (Thornton-le-Dale, Pickering, Helmsley and Grassington, to name a few). Our pace is leisurely. We stop for walks, for picnics, and to light candles in parish churches. Sometimes we stop for ice cream. We pass solitary farmhouses built of gray stone, sheep grazing in green fields bordered by hedgerows or stone walls, and once, we encounter a tractor parade. As always, we find many roses and only a few tiny thorns along the way.

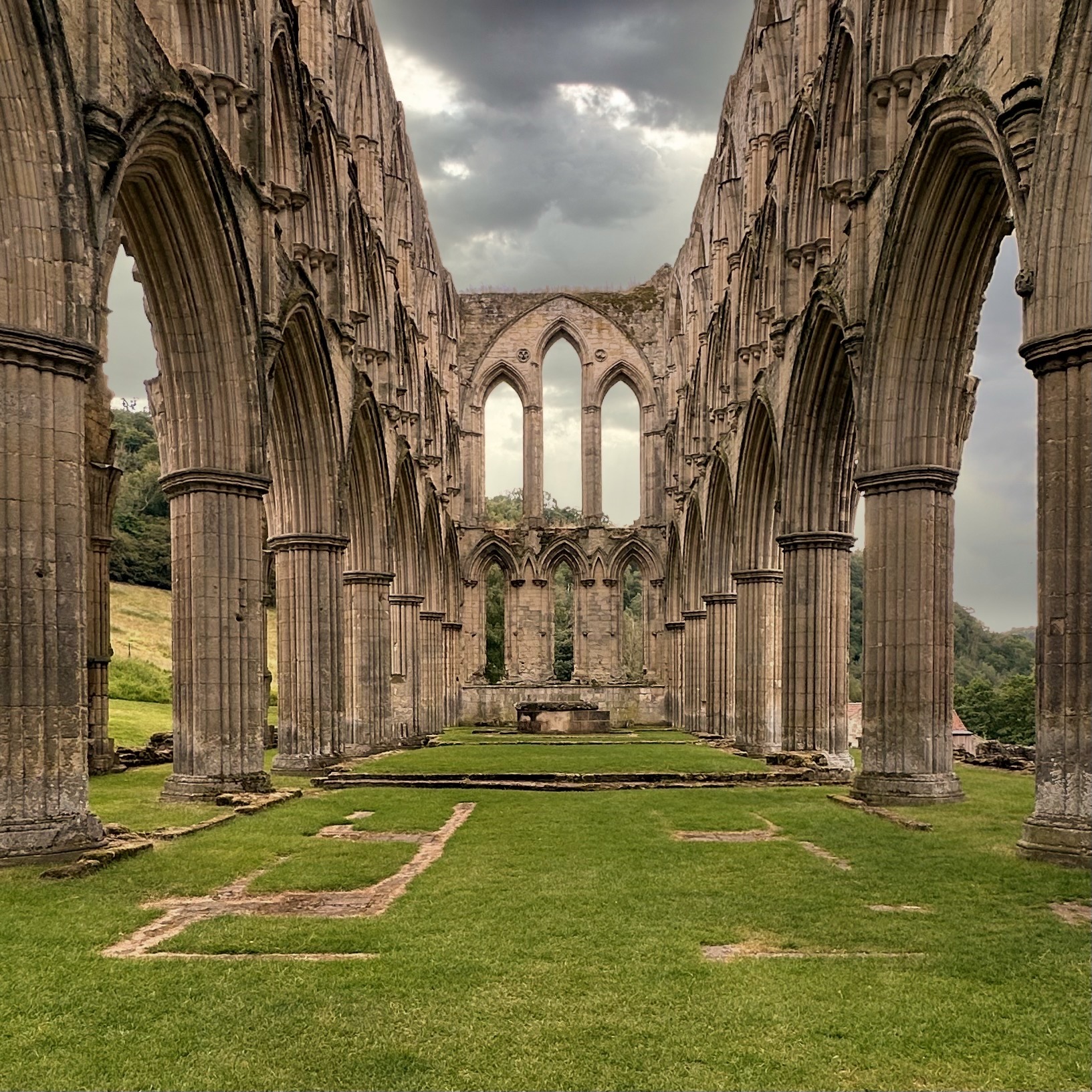

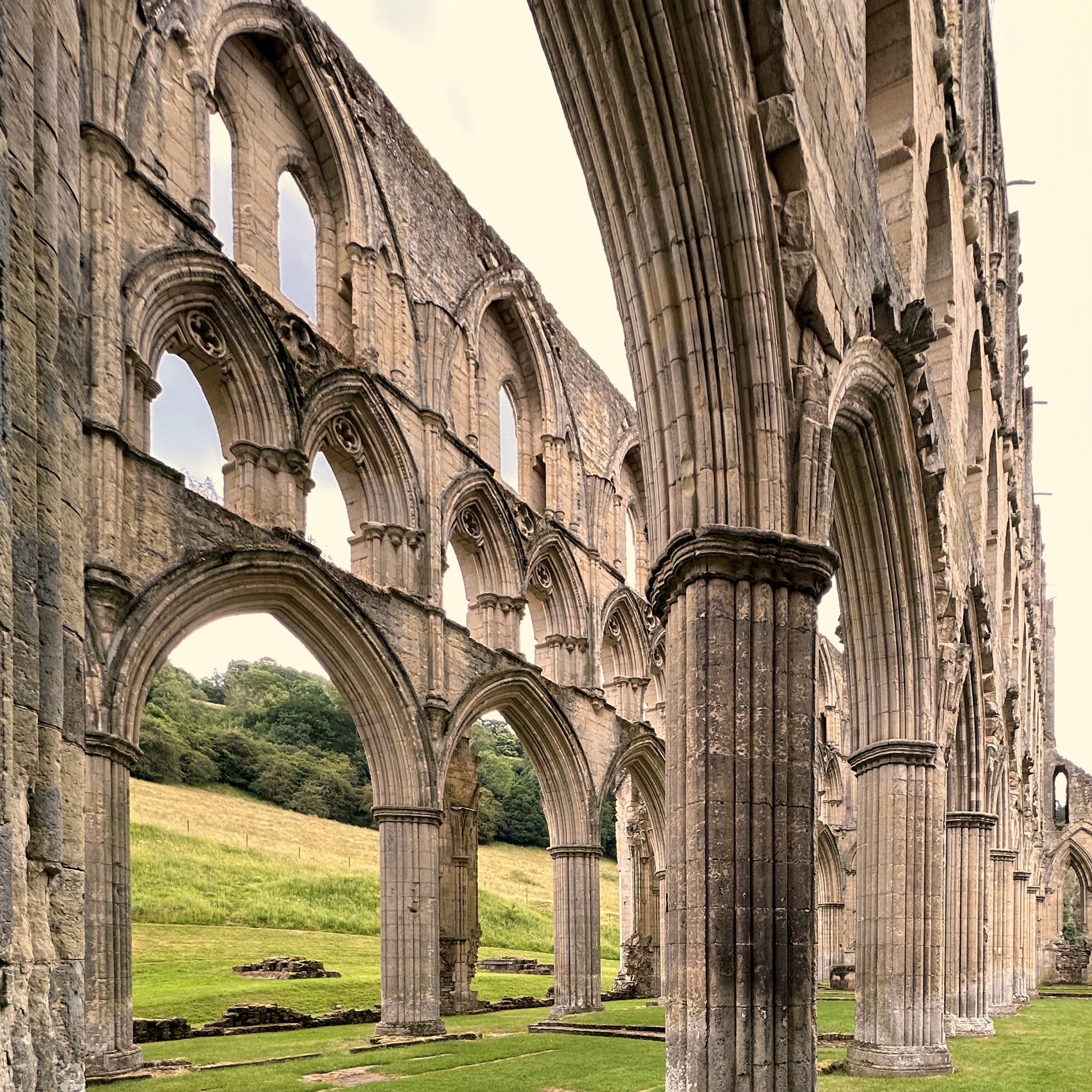

Rose: The eerie beauty of Rievaulx, a ruined Cistercian abbey hidden in an isolated river valley.

Rose: Three nights at the Durham Ox, a gastropub/hotel in the quaint hamlet of Crayke. The “cottage” Dave has booked consists of a ground floor sitting room, spacious modern bathroom, small fridge and sink, and two bedrooms upstairs. Our room price includes dinner and breakfast in the historic pub/restaurant with low, beamed ceilings, a huge walk-in fireplace, carved wood-paneled walls and flagstone floors. The pub is open all day every day, and is located just steps from our cottage door. Very convenient for takeaway pints.

Rose: A visit to the parish church in Crayke. After settling in at the Durham Ox, Anna sets off with candles and matches to see if the church door is unlocked. (Sometimes village churches are open, sometimes they aren’t.) As she starts up the hill, a white-haired gentleman exits his garden and begins walking in the same direction, at the same pace, on the opposite side of the single lane road. They walk abreast for a few minutes, and finally exchange a glance. “Going my way?” the man asks, a smile in his blue eyes. Anna laughs and explains where she’s headed. The man, whose name is Eric, produces a sizable skeleton key from his pocket. It looks heavy, and very old. “I’m just on my way to lock up the church for the night. I’ll show you around.”

A half hour later, Anna has not only learned about St. Cuthbert’s church (established as a sacred resting place in 685 for St. Cuthbert on his journeys between Lindisfarne and York), she has also learned about Eric’s two aunts who live in Arizona, the history of the uninhabited medieval castle at the top of the lane, how Eric and his wife moved to Crayke after they retired, and even the salacious fact that when scientists analyzed the exhumed remains of monks, a large percentage were found to have had syphilis. Perhaps Henry VIII’s rationale for the dissolution of the monasteries as corrupt had some basis in truth beyond his desire to sanction his divorce(s) and remarriage(s) and confiscate monastic wealth.

A Rose That Some Might Call A Thorn: A rainy day. Absolutely bucketing down. A perfect day for an indoor tour of Castle Howard, the immense 18th century stately home where the hugely successful 1981 TV production (and a later, movie version) of Evelyn Waugh’s novel “Brideshead Revisited” was filmed. Home to the Carlisle branch of the Howard family for more than 300 years, the rooms are full of priceless furniture, sculpture, paintings, and other relics, including sections of Roman mosaic tile.

Roses and Thorns: The rain stops in time for a walk before dinner. Anna consults her OS map and embarks on a circular walk. After fifteen minutes of joyful, easy walking along a flower-lined footpath, she hears the whirr of a strimmer, and comes upon a man in the process of clearing the path, which has disappeared into a mass of weeds. “Should I turn ’round?” she asks, “Or can I get through?” He shrugs. “You should be all right. It gets better a little further on.” But it doesn’t. Anna thrashes through stinging nettles and thigh-high grass for what seems like the length of a football pitch. The foliage finally gives way to a wheat field bordered by chamomile flowers, and so she carries on, her trousers drenched and legs stinging as if they’ve been attacked by a swarm of wasps. Past one field, then another, until an unmistakable odor signals that she has arrived at a field oozing with freshly spread manure. The stench is off-putting (to say the least) and the footpath seems to have petered out. So much for the idea of a circular walk. Best option is to turn around and head back to the pub for a well-earned pint of Guinness!

Roses from York: Before we even enter the historic section of town, Dave sees a barbershop, and can’t resist getting a trim. Did he need one? Debatable; he looks good either way! After a beer in the garden of the Fat Badger, we stroll atop the wall surrounding the medieval part of the city. From this vantage point, we gaze down at gardens and across rooftops to the towers of York Minster. It is one of the most important cathedrals in England, but it pre-dates the word “cathedral”, which came into use after the Norman Conquest, thus it is called a “minster”, as important churches were known in Anglo-Saxon times.

Inside the ancient monument, we admire its airy gothic interior, its rebuilt crypt, and especially, the recently restored Great East Window, the largest expanse of medieval stained glass in the country.

Culinary Thorns and Roses: Our expectations are too high for our meals at the Durham Ox. (Obviously, we have been spoiled by our meals in France and Edinburgh!) The breakfasts are delicious (choices include scrambled eggs with smoked salmon, avocado toast, eggs-over-easy, bacon, sausage, toast, marmalade), but the dinner menu and wine list are uninspiring. Anna solves the problem by ordering the same dinner—mussels marinière—three nights in a row, but Dave tries something different each night, and each time is disappointed. Fingers crossed we’ll have better luck in Wales, where we are headed next.

But first, our last stop in Yorkshire, the largest, best preserved and probably the most well-known monastic ruins in England: Fountains Abbey. Anna has vivid memories of coming here 50 years ago, on a family holiday. Since then, a visitors center has been built and the parking lot expanded, but the abbey ruins seem little changed, and remain as impressive as ever.

After two days in Edinburgh, we rent a car and cross the border to England, the land of Very Interesting Place Names. We begin compiling a list: Hartburn. Sheepwash. Wideopen. Haltwhistle. Once Brewed. Ladypark. Netherthong. Fatfield. Mold. Not making these up!

Rose: The sunny, warm weather persists. Rather unusual for the northeast coast of England, and almost annoying (but not really!), because the raincoats, fleece vests and waterproof boots we packed have been taking up space in our luggage.

Roses and Thorns: Dave has booked a one-night stay at a pub with rooms in a coastal village called “Seahouses”, reputed to be scenic and picturesque. It’s not. Dave takes one look at the dingy huddle of houses, shops and pub and says, “Let’s find somewhere else.” A quick internet search leads us to a lovely country house hotel where we manage to check into the last available room. But when we take our luggage upstairs, the room is stifling. Hot sun is pouring in, sunset isn’t for another five hours, and the large window only opens 3 inches. “It is never going to cool down in here,” says Dave. “Even if we borrow an electric fan. (A bit of back-story here: the unseasonably warm weather has meant lots of stuffy bedrooms and fitful sleep, and we are hoping for a good night’s rest.) Feeling limp from heat, hunger and thirst, I am inclined to surrender and make the best of the situation, but Dave perseveres. “Wait here,” he says, and disappears downstairs to Reception to see if there is a suite or something we can upgrade to. But it is not to be. “There are no other rooms,” he informs me when he reappears. “I’ve checked out and gotten our money back. Let’s go.”

By now it is after 6 pm, and I am hoping that we won’t be spending the night in our rental car. A short drive along a wooded lane leads to another country house hotel. This one has recently been refurbished and actually has an air-conditioned room available on the ground floor with a terrace overlooking a green field. And it costs less than the hot, stuffy place. Heaven! Way to go, Dave! Sometimes it pays to be tenacious.

Rose: Our picnic lunches continue in various locales, always convenient; sometimes scenic. Afterwards, Dave typically seeks out a shot of espresso, easily done in France, but here, not so much. Until one day we stop for gas, and in drowsy post-prandial desperation, Dave buys a macchiato from a machine dispensing Costa Coffee and discovers it tastes exactly the way he likes it. Available at petrol stations all over England, Dave will enjoy many such automated Costa Coffee macchiatos, and he will never be disappointed

Rose: The serene countryside setting of Swinburne Castle, where Dave has booked us a two-night stay. Worn stone steps lead upstairs to our rooms in a converted stable block dating from the 17th century. Our bedroom windows look out over a seemingly endless expanse of parkland, majestic copper beeches and oak trees.

After settling in, Anna heads out for a walk, and is immediately accosted by Millie and Daisy, the resident mutts, who vie for her attention. After administering a belly rub to each dog, Anna sets off again, only to meet up a pack of beagles and their two handlers, approaching from the opposite direction. The dogs politely keep their distance while Anna chats with the men. It is a hot day, and one of the men explains that they’ve just taken the dogs to the “burn” (river) for a dip. “May I pet them?” Anna asks. “If you let one near, they’ll ALL want to know ye,” the handler answers, and indeed, as soon as Anna invites one hound to come closer, they all take turns leaping up, tails wagging. Pure joy, both canine and human.

Thorn: Weak, spotty internet during our stay at Swinburne Castle. We have great difficulty accessing regional maps, the weather forecast or even email, and Anna loses an afternoon’s worth of work. Perhaps it is the price we pay for a tranquil setting: the more remote a location, the less connectivity.

Roses: Roman ruins of Corbridge and Housesteads, a walk along sections of Hadrian’s Wall and The Sill, an impressive escarpment along part of the wall. We never fail to be awe-struck by the extent of the Roman empire, and the remnants that still exist, two thousand years later.

Rose: Passing through Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, we make a slight detour to Gateshead in order to visit a landmark piece of public art, the “Angel of the North”. This 65 foot-tall metal statue is as much a part of this region’s identity as the Statue of Liberty is to New York. It is also instantly recognizable to fans (like us) of Vera, the curmudgeonly detective played by Brenda Blethyn in the long-running British television program of the same name. Designed by sculptor Antony Gormley, the statue is made of Cor-ten steel, and stands on the former site of colliery pithead baths. According to Gormley, the angel has three functions: to remind us that below this site coal miners worked in the dark for two hundred years, to illustrate our transition from the industrial to the information age, and to provide a focus for our future hopes and fears.

Rose: Coastal village of Staithes, birthplace of Captain Cook, the son of a butcher who decided he preferred life at sea, so he joined the navy and eventually discovered Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii and many other small islands in the Pacific. He also brought new diseases that wiped out almost half the populations of the places he visited, but that’s another story.