La Côte d’Or

Five days in, and we have recovered a few IQ points lost to jet lag, though most mornings, our brains still feel smothered in cotton wool. Could it be the wine? Surely not.

The day we depart Chablis, we rendez-vous for lunch with Anna’s brother Lon and his friend Kate, who also happen to be in France. The four of us enjoy a leisurely meal and are very pleased indeed to share time together in France. After coffee and dessert, we go our separate ways and as soon as we get a few miles down the road, we kick ourselves for not taking a photo of our reunion. For the record, we met in the village of Collanges-la-Vineuse, southwest of Chablis in an area of tree-lined roads, vine-covered fields, and the occasional cherry orchard.

We continue southeast into the region known as La Côte d’Or (golden hillsides). Repeating patterns of vines cover the hilly green terrain like patchwork. Red tile-roofed houses cluster around tall church steeples. The soil changes from the pale chalky clay of Chablis to a loamy dark caramel. Lilac blossoms—white, lavender and deep purple—seem to decorate every roadside hedge and garden. In one tiny village we come upon a collection of antique chauffrettes (metals pots that are filled with slow-burning paraffin to keep the vines warm against frost), arrayed on top of an old stone wall.

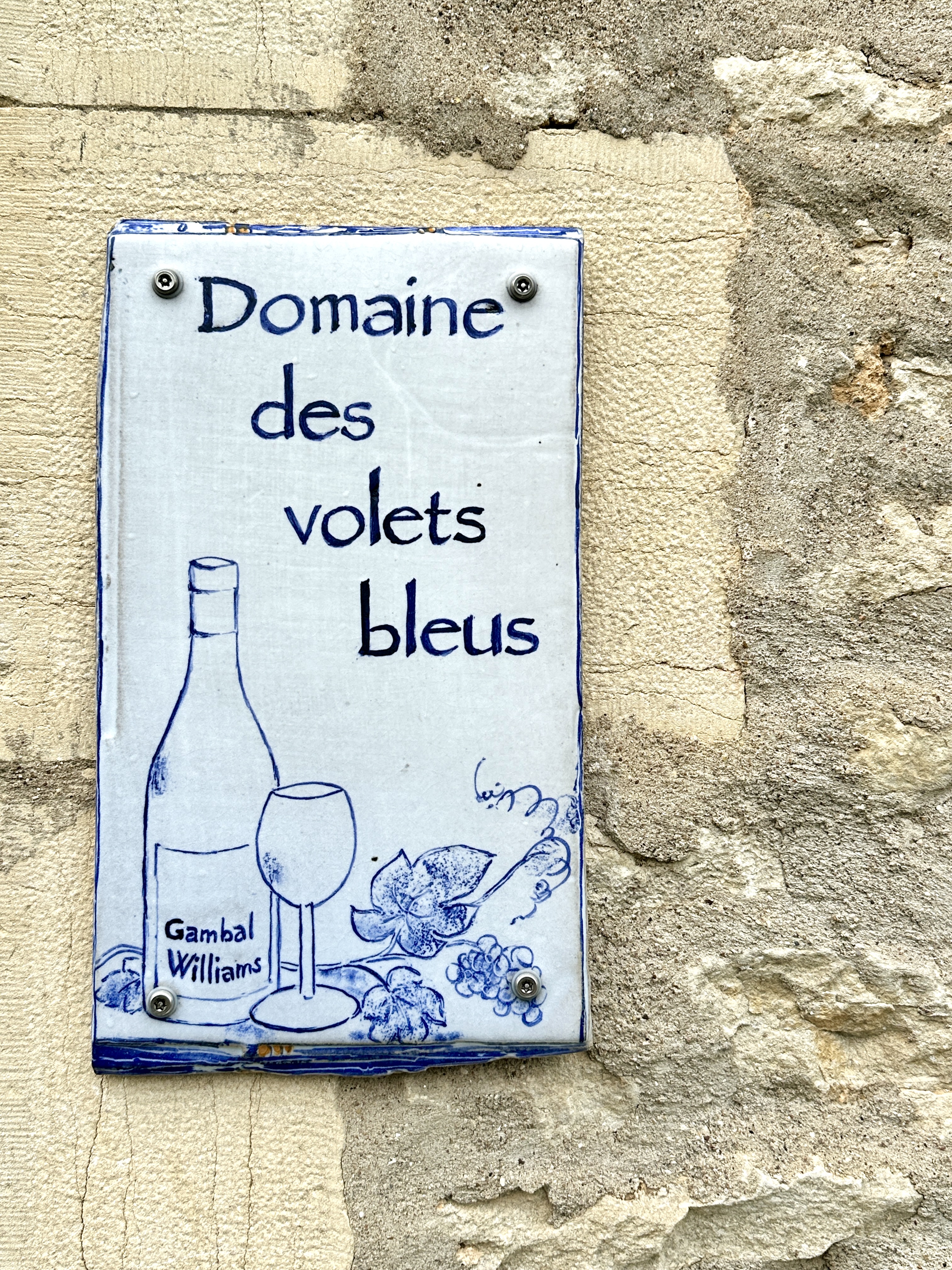

Our destination is Domaine des Volets Bleues in Orches, a rental house in a secluded hamlet consisting of about a dozen dwellings tucked into the lee of a steep cliff. We will stay here five nights, per Anna’s request for this trip to be less peripatetic than previous travels, and we are both looking forward to staying in one place and embarking on day trips to explore the region.

A narrow lane with a steep hairpin turn leads to the house. Uncertain where we should park, we stash our car around the corner a few meters away and walk to the front door. As we approach, a short, wiry woman with close-cropped grey hair steps into the road, draws a quick puff off her cigarette and tosses it to the ground. She grinds the cigarette butt with her foot and barks, “Where did you park your car?” We presume she is our host, despite the lack of friendly preamble. (No “Hi, you must be Dave and Anna?” Not even a “hello”?)

Never mind. As soon as we follow her into the flagstone-floored entry, the brusque greeting hardly matters. The house dates from the 16th century, and has been carefully renovated to retain period details such as exposed stone walls and soaring ceilings supported with beams the size of entire oak tree trunks. Modern conveniences have been thoughtfully added: well-appointed kitchen and bathrooms, a washer/dryer and super-fast internet. Furnishings and décor are artfully curated and convey a comfortable yet stylish “lived-in” feel; it is obviously someone’s home, not just a rental unit.

Our host gives us a quick tour, thawing only slightly when she realizes that we are not strangers to France (or to England, where she is from) and so she won’t have to explain all the basic ins and outs of local culture (such as shops closing for lunch and restaurants often closing on Mondays). We soon discover that she is not the owner of the house, but the property manager, who, along with her husband, oversees about 24 properties. (Thus explains—sort of—her gruff welcome.)

The owner of the house, Alex Gambal, is an American who moved to France with his family 30 years ago to become a winemaker. He has written a book recounting his experiences, “Climbing the Vines in Burgundy” and has left a copy for us to browse. The book could use some editing, Dave says, but is nevertheless a fascinating read.

We wake up our first morning at Domaine des Volets Bleues to find the internet down due to a system-wide network outage. A weak phone signal means tethering to our phones is not a viable option, and First World Problems ensue: We can’t read the New York Times, send or receive emails, edit photos that upload to the cloud, research our sightseeing plans or even check the weather forecast. Anna can’t post to her blog or attend her British Book Club via Zoom. However, we are still on holiday in France, so it’s not all bad. Besides, internet outages are usually sorted within a few hours, right? (Wrong. Spoiler alert: We remain offline until we depart, four days later. This is unexpected, and a bit inconvenient, but it does not dim our appreciation for the lovely house and region. And, we remind ourselves, one of the requirements of travel is a willingness to cope with the unforeseen.)

We head to Beaune, a prosperous town known as the epicenter of Burgundy wine, park the car and explore the old town on foot. The famous Hospices de Beaune with its magnificent Burgundian tile roof lives up to the hype of its being a masterpiece of medieval architecture. Founded in 1443 as a hospital for the poor and orphaned, the hospital remained in continuous use through World War I, when the nuns cared for injured servicemen.

While in Beaune, we enjoy a delicious bistro lunch of seared tuna salad (Anna) and steak tartare avec frîtes for Dave.

Another day, we have booked a “tasting workshop” at Dufouleur Frères in Nuits-Saint-Georges. At the appointed hour we drive through the gate and meet our energetic young host, Jean Dufouleur, one of the many cousins descended from generations of winemakers. The family name—Dufouleur—he informs us, comes from the word for a person who stomps on the grapes to make wine—un fouleur—grape crusher. We learn how he came to be an oenologist—a scientist of wine and winemaking—and about his vision of an environmentally-sustainable future for his family’s winery. On a large map, Jean points out the region’s different vineyard plots (called climats), and explains that white Burgundy wines depend as much on the producer’s methods and intentions than a given terroir. Dave is familiar with various winemaking techniques, but Anna is interested to learn that while terroir supplies the raw materials, the élevage (aging and finishings processes) can make—or break—great wine.

Most mornings, Dave finds a new boulangerie (bakery) to sample, and we manage to squeeze in at least one more wine tasting.

One lunchtime, Dave is tempted by a restaurant whose menu lists about 15 varieties of pizza. “I’d love a pizza”, he says. Anna has her doubts, but the menu also offers a couple of salads, and so she agrees to give it a go. The look on Dave’s face says it all: pizza, like many things, is different in France.

It might seem like all we are doing in France is eating and drinking, but we also spend plenty of time exploring, on foot and by automobile.

Obviously, we spend a bit of time making photos. Dave prefers the challenge of composing landscape shots; Anna is drawn to details.

Finally it’s time for the “Anna Roots Tour”. She has fond memories of living in a large apartment above the stable block of the Chateau Dracy-les-Couches, preparing a fleet of bicycles and getting to know her fellow bike tour guides. She has always thought she might visit again someday. But on this cold, rainy afternoon 35 years later, the place only looks vaguely familiar, and Anna feels no nostalgia, rather a sense of contentment to have “been there, done that”, and to now be in a different place and time of life.

On our last evening before departing our blue-shuttered domain, we dine at Le Bistrot des Falaises (the cliffs bistro), in the nearby hamlet of Saint Romain. Our meal is a revelation of fresh seasonal ingredients and inventive combinations. Anna chooses an Entrée + Plat of herring, beet and radish salad, followed by grilled octopus and braised endive in a reduction sauce. For Dave, Plat + Dessert: steak tartare and garlic roast potatoes, followed by rhubarb tart in an almond crust, garnished with a cream sorbet.

The next morning, we wake to the sound of a cuckoo calling. It is a rare and charming sound, a gentle reminder that it’s time to pack up and move on to a new destination. (Hopefully with internet access.) We’re going to stay three nights in the capital French gastronomy, Lyon. Will it live up to its reputation, and will our stomachs be up to the task of finding out?

Leave a comment